How Housing Insecurity Drives Latino Immigrant Children’s Labor in California

Executive Summary

Unaccompanied children migrating to the United States—most of whom are from Latin America—face significant risks of labor exploitation, injury, and even death. This study examines housing insecurity in the United States as a root cause of why these children end up in dangerous jobs. It also identifies the most effective areas for policy intervention.

Through interviews with 45 service providers across California—including attorneys, social workers, educators, and advocates—the study highlights a key finding: the lack of safe and stable housing is a leading factor driving unaccompanied immigrant children into exploitative work.

Federal law requires the government to place unaccompanied children with sponsor households, often families who are undocumented Latino immigrants. These sponsors frequently experience severe financial strain, housing insecurity, and labor exploitation themselves. When unaccompanied children join these households, they do so without any financial resources, instead adding new costs to the household economies that can thrust families into further economic hardship, which has a ripple effect:

- Children are pressured to work to help cover rent, especially when landlords impose illegal rent hikes or threaten residents with an unlawful eviction after an additional resident is added to the household, or sponsors expect financial contributions from children once they turn 18.

- Some children work to escape abusive or unsafe living environments, including cases of domestic violence, sexual abuse, or labor trafficking by sponsors.

These challenges push children into low-paying, hazardous jobs in industries such as agriculture, construction, fast food, and gig work, often at the expense of their education and well-being.

To address this crisis, the study calls for action in key areas:

- Expand affordable housing: Increase emergency housing options for vulnerable families and youth. Develop emergency housing assistance and create more shelters for homeless and runaway children for immediate relief. Build new affordable homes for sustainable relief in the longer term.

- Provide financial support: Offer emergency rental assistance and downpayment aid, regardless of legal status, to support housing stability and child well-being for children across the state.

- Strengthen legal protections: Increase funding for housing code enforcement agencies to improve staff inspection and compliance teams. Push for immigration reform to provide legal status for long-standing immigrant families who serve as sponsors, enabling them to access critical housing resources and protections.

- Offer legal aid: Expand federal and state-funded pro-bono legal representation for undocumented immigrant families and unaccompanied minors to combat labor and housing rights violations, and secure representation for children who have experienced forced labor and trafficking.

- Support families and youth well-being: Improve efficiency in spending by developing a wraparound support network for unaccompanied children and their families. Enhance non-legal services such as healthcare and education enrollment and completion supports.

By addressing the root causes of housing insecurity and its cascading effects on child labor, policymakers can help ensure a safer, more stable future for unaccompanied children and their families. In doing so, they will ensure a safer, more stable future for all California residents.

Introduction

There has been an alarming rise in child labor exploitation and related injuries and deaths in the U.S. over the last decade.1 Since fiscal year 2015, the number of children employed in violation of child labor laws has risen by 283 percent, from 1,012 cases in 2015 to 3,876 by 2022.2 In fiscal year 2023, 955 cases of child labor violations were reported across the U.S., affecting the lives of an estimated 5,792 unlawfully employed children.3 And, in 2024, another 736 cases of child labor violations were closed, affecting the lives of 4,030 children. By mid-2025, over 1000 child labor violation cases had been reported and remained open.

Among the children at risk of labor exploitation are immigrant children, including unaccompanied minors. Almost 80% of unaccompanied children apprehended in the U.S. are of Latin American origin, migrating primarily from Guatemala (42%), Honduras (28%), El Salvador (9%), and Mexico (8%).4 Federal law requires that unaccompanied child migrants be placed in the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) and then eventually placed with an adult sponsor.5

When a new child joins a household, it can create additional financial, legal, and social challenges for the family. Since unaccompanied children’s sponsors tend to be long-settled immigrants, including many undocumented immigrants, recent arrivals are likely to enter into households in which sponsors are themselves being exploited for their labor, facing food and housing insecurity, and experiencing health-related challenges.6 Latino immigrants’ migration histories, labor market constraints, and enduring insecure legal status have resulted in Latinos making up half of California’s impoverished population—a condition worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic.7 Today, an estimated 16% of Latinos in California live in poverty.8 According to LPPI, about 59% of Latinos in California, compared to 55% of all California residents, are housing cost-burdened, meaning they spend over 30% of their income on housing.9

Since unaccompanied children are not recognized as refugees upon their arrival in the U.S., few services exist to support them and their sponsors. For example, unaccompanied children cannot access services such as housing and cash assistance, nor protection from deportation, as refugees receive. Instead, only a select number of children receive federally funded Post-Release Services, mainly virtual check-ins and case management.10 They are promptly placed in removal proceedings following their release from federal custody, where they have the chance to make an asylum claim if they fear persecution upon return to their country of origin.11

In most cases, the responsibility of meeting unaccompanied children’s multiple legal and non-legal needs, such as obtaining legal representation and school and health-care enrollment, falls on children and their sponsors. Add to this the immediate financial costs of repaying migration debt—that is, the money the unaccompanied child owes their coyote, a migration guide, for the journey to the U.S., which many children often repay themselves—and the longer-term routine cost of integrating an additional member into the household. Yet undocumented and mixed-status immigrant families can have unstable and unpredictable ties to formal support institutions, as families are inconsistently eligible for social support services and fear being labeled a public charge, that is, an individual dependent on government support for basic needs.12 For noncitizens, public charge is grounds for individuals to be denied a green card, visa, or admission to the United States.13

These families also contend with the fear that their engagement with formal institutions can trigger deportation and family separation,14 a fear made increasingly more real under the openly anti-immigrant federal administrations. In all, the needs of unaccompanied children and their sponsors are high. Yet, their access to legal and non-legal services to support children’s integration and well-being is inconsistent, causing families to rely on children to support themselves and the household.

Data and Methodology

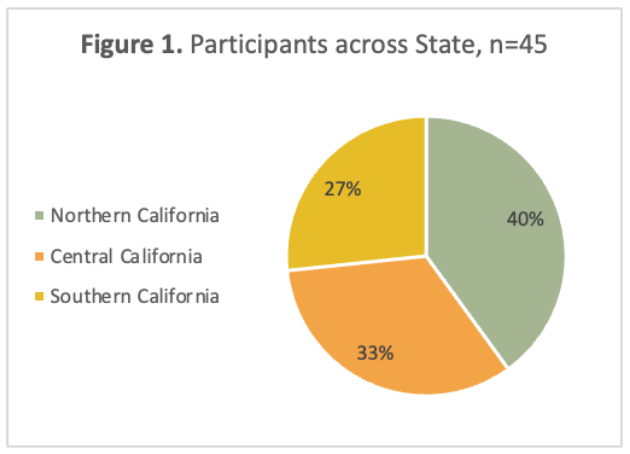

This study draws on interviews with 45 service providers working with unaccompanied children across California. Of these providers, 18 were based in Northern California, 15 in Central California, and 12 in Southern California (see Figure 1).

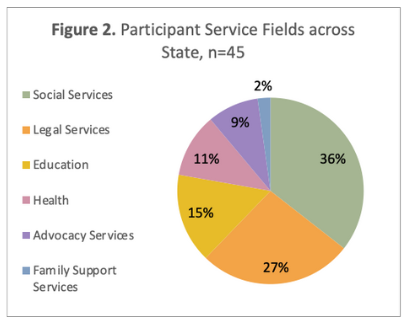

Study participants included legal service providers, (attorneys and paralegals); physiological and psychological health care providers; educators (school district officials and staff and teachers); social service workers (case managers, social workers, family service experts, and one financial educator); and advocates specialized in anti-trafficking and housing rights organizing (see Figure 2). Interviewees were asked about the most salient needs prompting children to enter exploitative jobs.

Immigrant Families and Communities Facing Housing Insecurity

Regardless of region or field, service providers unanimously identified the lack of access to safe and stable housing as the primary driver of children’s entry into dangerous and exploitative work across the state. Yet insecure housing stems from other broader issues, including low-wage immigrant worker exploitation, housing shortages, and landlords’ violation of renters’ rights.

Immigrant workers, particularly in agriculture, are especially vulnerable to housing insecurity due to exploitation in the labor market and limited access to housing assistance. Industries such as agriculture and farming notoriously exploit workers by paying them less than minimum wage. In California, an estimated nine in 10 farmworkers are immigrants.15 Among them, eight in 10 are undocumented. Underpayment and wage theft make it difficult for immigrants to afford safe and stable housing. Undocumented immigrants’ legal status also disqualifies them from federal housing assistance.16 Undocumented immigrants thus experience disproportionate housing cost burdens.17 Since agriculture dominates much of Central California’s regional economy, immigrant families—and therefore unaccompanied children—in the Central Valley are vulnerable to labor and housing exploitation.

Multiple immigrant families can often share single rental units, working more than one job, and face difficult decisions between paying rent and providing food to make ends meet.18 In Northern and Southern California regions, where immigrant communities are concentrated in dense urban neighborhoods, unaccompanied children arrive at overcrowded apartments and schools. High population density and low affordable housing supplies result in parents and other adult caregivers working multiple jobs to afford expensive rental units, however dilapidated and dangerous they may be. In Central California, the low rental housing supply and the distance between safe housing and the farms where most sponsors and children work make the cost of living expensive. A Central Valley housing advocate, Nancy, noted, “Families have to go beyond working two jobs, two or three, maybe even four jobs and having a bunch of side hustles to make ends meet.” Heads of household are caught “figuring out ‘do I pay rent, or do I provide food for my family?’”

Meanwhile, landlords frequently violate the housing rights of low-income, undocumented, and non-English-speaking tenants, exacerbating housing insecurity for these groups. For example, landlords often raise rent unlawfully, refuse to make needed repairs, and threaten unlawful evictions. Undocumented and mixed-status immigrant families’ fear of retaliation stifles their ability to resist such abuses of their housing rights. Service providers reported instances of landlords explicitly threatening to report families to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Given that 44 percent of the state’s households are renters,19 service providers described landlords’ persistent violation of tenants’ rights as a leading culprit of housing insecurity and, therefore, child labor in the state.

Housing Insecurity Driving Child Labor in California

Housing insecurity among adult household heads directly influences children’s entry into exploitative, low-wage work, especially for unaccompanied immigrant children. For these children, the jobs are exploitative and dangerous: Immigrant children work in agriculture and farming, construction, fast food and restaurants, and the gig economy, such as app-based food delivery services using profiles of familiar adults. Many unaccompanied immigrant children have prior work experience in their countries of origin, and 67 percent are over 14 years old. Immigrant children work these jobs to mitigate two types of housing insecurity: (1) the looming loss of housing and (2) the threat of unsafe living conditions.

1. The Looming Loss of Housing

For many immigrant children, general feelings of housing insecurity are compounded by cultural expectations and the pressure to find independent housing as soon as they turn 18. Service providers described that some children feel indebted to sponsors and thus work to make up for additional expenses, including illegal rent increases, incurred on their behalf. Loss of housing also looms over transitional-age youth who face cultural expectations of independence at age 18. Service providers described dozens of instances in which unaccompanied children shared that their sponsor expected them to find independent housing at the age of 18 to alleviate the household of the young person’s cost of living. This is especially true for young men encouraged to see themselves as independent and self-sufficient in their transition to adulthood. Children might begin working years before their 18th birthday in anticipation of this eventuality.

Service providers noted that children often worked at the expense of their schooling but still identified housing, not education, as the primary basic need that unaccompanied children lacked. Sarai, a Northern California case manager, described the negotiations she and her colleagues had to make with unaccompanied children who prioritized work over education. While service providers recognized the need for children to work to stabilize their home lives, but consistently asked themselves, “How do we create the basic and fundamental things that kids need?” Service providers across California agreed that the only way to ensure children could focus on their futures (education) was by securing their present through access to “housing, food, and basic things […].”

2. The Threat of Unsafe Living Conditions

Even if children have the promise of housing, they may begin working to escape the abusive living conditions in their sponsor’s household, such as domestic violence and forced labor. Some children are guaranteed housing provided by their sponsor, but the living conditions are hostile or abusive, prompting the child to work to achieve early independence. Unaccompanied children may experience domestic and sexual abuse, especially when released to non-parent and unrelated adult sponsors. The risk of abuse increases when sponsors live in complex households with additional unrelated adults.

In severe circumstances, some children are housed by sponsors intent on trafficking them for cheap labor. Some children are bound to their sponsor’s household and forced to provide childcare or housekeeping within the sponsor’s home. Others are forced into hazardous agriculture, farming, and construction work, or service work in restaurants, landscaping, and janitorial work. Under these circumstances, wages are paid directly to their sponsor. Sponsors may give the child a small sum of their earnings. In most cases, however, the child is left penniless and reliant on the sponsor. Forced labor and trafficking often drive children to run away.

According to an anti-trafficking child advocate named Priscilla, safe housing is the most critical need for children escaping forced labor and trafficking. However, Priscilla recognized that longer-term relief services were essential for children to grow and develop in healthy and positive ways. As such, she explained that access to legal representation could support children’s application for asylum or some other form of protected legal status. Furthermore, mental health services to overcome trauma stemming from children’s trafficking experiences would help young people adjust to their new lives.

Policy Recommendations

Moving beyond the finding that children are engaged in child labor, this research set out to understand housing as a root cause of migrant child labor in California to offer solutions. State and regional policymakers, organizers, and advocates focused on immigrants and immigration should collaborate with housing experts on efforts to end child labor. Aside from constructing more and more affordable housing across California through an Affordable Housing Trust Fund,20 the findings above suggest the need for increased funding for and the development of the following efforts:

States and counties can work together to:

- Strengthen a Youth Shelter Network across the State: The California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) can strengthen the effectiveness and efficiency of its shelter network by providing youth-centered services to homeless and runaway youth, particularly those fleeing forced labor and trafficking, that offers immediate housing solutions. This effort can support the three-year “Action Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness” by the California Interagency Council on Homelessness.

- Para Los Niños, a Los Angeles-based organization, coordinates a county-wide shelter list for transitional age youth that can offer a potential model for a statewide initiative. HCD can partner with community-based organizations to replicate the shelter list in other counties across California, formalizing state-county partnerships to address housing needs. HCD can then leverage the California Department of Social Services’ CalNEW Program network to notify California students of housing resources, thereby linking basic needs and child development providers’ efforts. Immediate relief and safe spaces are essential to protect children from exploitative work environments. State-county partnerships to develop county-wide shelter lists offer an additional opportunity to map where California has established resource oases and deserts for targeted investment in community-based efforts to address housing insecurity.

- Provide Emergency Rental Assistance for Families Regardless of Immigration Status: Stable housing gives children a safe place to grow, explore, rest, and build trusting relationships with kin and communities that shape positive self-concept, behaviors, and aspirations for the future. California can offer all children stable housing by expanding state-funded emergency rental programs, including Emergency Housing Vouchers, to address the housing instability exacerbated by the pandemic and climate crisis. Immediate financial relief will reduce pressures that push children into exploitative labor.

- California legislators might consider expanding CalWORKS benefits to undocumented immigrants who contribute $8.5 billion in tax revenue in California each year.21 Alternatively, California can prioritize offering housing assistance in cities where unaccompanied children are most frequently released to sponsors. The top five receiving counties in California are Los Angeles, Alameda, Orange, Santa Clara, and San Mateo.22 The California Department of Housing and Community Development can collaborate with community-based organizations and schools partnered with the California Department of Social Services through the CalNEW and Opportunities for Youth programs to leverage trusted community networks in high-need regions. Local governments—city and county-level offices—could expand existing initiatives, like the California Department of Social Services’ Independent Living Program, and/or coordinate new initiatives in high-need cities that align best with the local fiscal climate but that include immigrant children with temporary or without legal status.

- California legislators might consider expanding CalWORKS benefits to undocumented immigrants who contribute $8.5 billion in tax revenue in California each year.21 Alternatively, California can prioritize offering housing assistance in cities where unaccompanied children are most frequently released to sponsors. The top five receiving counties in California are Los Angeles, Alameda, Orange, Santa Clara, and San Mateo.22 The California Department of Housing and Community Development can collaborate with community-based organizations and schools partnered with the California Department of Social Services through the CalNEW and Opportunities for Youth programs to leverage trusted community networks in high-need regions. Local governments—city and county-level offices—could expand existing initiatives, like the California Department of Social Services’ Independent Living Program, and/or coordinate new initiatives in high-need cities that align best with the local fiscal climate but that include immigrant children with temporary or without legal status.

- Strengthen Housing Code Enforcement and Tenant Education of Housing Rights: Adequately staff enforcement units within the California Department of Housing and Community Development to ensure landlords maintain safe and secure housing and adopt anti-displacement protections. Slum housing managers should be sanctioned for violating California housing policies and violating California tenants’ housing rights. State officials can partner with local, community-based organizations to offer culturally responsive Know Your Rights trainings for tenants across the state, adapting the California Department of Health Care Access and Information’s Community Health Workers, Promotores, and Representatives program to serve California residents with culturally responsive and language-diverse housing education programming. Philanthropic foundations and leaders should increase funding opportunities for community-based organizations to apply for resources that would allow them to grow their language translation services teams. With greater linguistic representation in organizations, community advocates can better disseminate critical and timely housing rights information while creating opportunities for residents to report housing rights violations.

- In the Central Valley, where housing on farms is primarily overseen by local Environmental Health Divisions in collaboration with the HCD, the state should take increasing precautions to ensure safe and sanitary housing for farmworkers and their children. This should include proper roofing, flooring, temperature-controlled ventilation, running water for farmworker safety and sanitation, and promotion of dignity and respect.

- Develop a Statewide Legal Service Network: Increase funding for low- and pro-bono legal assistance for immigrant communities across California. For those experiencing insecure housing or violating their tenants’ rights, legal representation can ensure tenants’ rights are upheld, improve housing stability, and prevent retaliatory actions by landlords. Access to legal representation for California residents of immigrant backgrounds will help reduce housing insecurity and child labor risk for vulnerable populations without fearing the threat of deportation. Legal representation could also bolster undocumented immigrants’ likelihood of pursuing workplace violations, including wage theft and other forms of exploitation, extortion, and trafficking, all of which are connected to immigrant children’s employment in hazardous occupations in violation of their labor rights. Recognizing that California suffers from spatial inequality in immigrant legal (and health) services, current and future efforts should bolster California’s legal service network to ensure equitable access to legal aid across rural and urban geographies.23

- Legal representation for unaccompanied minors is essential for their overall integration, development, health, and well-being. Yet, in 2025, the federal administration began rolling back the limited federally funded legal aid initiatives geared toward unaccompanied children. These included Know Your Rights presentations for up to 100,000 children and pro-bono legal representation for 26,000 children at the time of funding termination. Without legal representation, children have a higher chance of being deported to the countries they fled and trafficked for labor. California has the opportunity to intervene, providing state-funded legal representation for unaccompanied children as a model for other states. If the recommendations above are heeded, the state’s newly developed youth shelter network and CalNEW school sites could serve as important referral sites. Philanthropic leaders can prioritize funding to legal aid organizations, law school clinics, and advocacy networks to support pro bono legal representation to unaccompanied children and their caregivers.

- Legal representation for unaccompanied minors is essential for their overall integration, development, health, and well-being. Yet, in 2025, the federal administration began rolling back the limited federally funded legal aid initiatives geared toward unaccompanied children. These included Know Your Rights presentations for up to 100,000 children and pro-bono legal representation for 26,000 children at the time of funding termination. Without legal representation, children have a higher chance of being deported to the countries they fled and trafficked for labor. California has the opportunity to intervene, providing state-funded legal representation for unaccompanied children as a model for other states. If the recommendations above are heeded, the state’s newly developed youth shelter network and CalNEW school sites could serve as important referral sites. Philanthropic leaders can prioritize funding to legal aid organizations, law school clinics, and advocacy networks to support pro bono legal representation to unaccompanied children and their caregivers.

- Invest in Non-Legal Human Services to Bolster Child Safety and Well-being: Increase funding for holistic child-centered programming for unaccompanied children and their sponsors in the state. Such programs include the California Department of Social Services Opportunities for Youth Program, which enhances community-based services such as case management, social work, and child advocacy to help families access essential resources such as food, health care, and emergency housing. This support will reduce financial strain on families and child labor risks, thereby reducing potential future costs to the state.

- Unaccompanied children endure violence, poverty, and other adverse experiences, like abuse and neglect, before, during, and after migration. Children who work in hazardous, low-wage labor in the U.S. endure the added trauma of exploitation by adults whom they trusted with their care. An investment in holistic, child-centered human services can reduce state-incurred costs associated with later life unemployment, homelessness, and risky behaviors associated with unattended trauma and mental health illnesses. Localities across the state can develop holistic “one-stop-shop” service centers like the City of Los Angeles’ FamilySource Centers, which offer free services to low-income city residents. In Los Angeles, FamilySource Centers can partner with organizations serving unaccompanied children, like Esperanza Immigrant Rights Project, the Central American Resource Center, and others, to increase immigrant families’ awareness of existing services. The City should consider partnering with school districts to develop school-based YouthSource Centers to eliminate children’s need to miss school days in whole or in part to attend legal and social service appointments, thereby increasing school enrollment by pairing meeting children’s short-term needs (e.g., housing, legal, and other forms of aid) with their long-term investments (e.g., language learning and educational attainment).

Additionally, state legislators can support AB 1840, California Dream for All, which offers a downpayment assistance program for California residents regardless of legal status. California legislators have also proposed other forms of support for homeownership in the state, to help families live outside of complex households. For these to be successful, state legislators should collaborate with community-based organizations and housing advocates to run public campaigns to garner statewide support. Importantly, homeownership support would greatly benefit even U.S.-born individuals who are migrating from California to other states at steady rates each year.24

Federal legislators can effectively disrupt migrant child labor through the passage of immigration reform policies, mainly through the provision of legal relief to the thousands of immigrant families who have been in the U.S. for over one decade and are now serving as sponsors for unaccompanied children released from ORR custody each year. Immigrants with protected legal statuses are paid higher wages and are more likely to report labor violations. Legal status will also allow formerly undocumented heads of households to qualify for federal housing programs.

Federal legislators might also consider more long-term responses to support the integration of unaccompanied minors, beyond the case-management services offered to a minority of unaccompanied children released to sponsors in the Central Valley of California, as in the rest of the state and indeed the nation. Universal and holistic post-release services—including government-provided legal representation, mental and emotional health services, financial assistance, educational enrollment, and family integration and conflict mediation support services—will create a human services safety net that protects the greatest number of unaccompanied children from exploitative child labor.

Finally, the federal government must work diligently with industry leaders, community organizations, and policymakers across state and local governments to increase housing supply and lower housing costs. In 2025, the U.S. faced a 4.5 million-home shortage. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce surmised that “balancing housing supply with growing demand is essential for improving affordability, driving economic growth, and supporting workforce mobility.” While the housing crisis is not strictly an issue faced by Californians, the state, which hosts the fifth-largest economy in the world, can offer a bellwether for the nation.

References

1 Hannah Dreier, “Alone and Exploited, Migrant Children Work Brutal Jobs Across the U.S.” The New York Times, February 25, 2023, available online.; Hannah Dreier, “The Kids on the Night Shift,” The New York Times, September 18, 2023, available online.

2 Jennifer Sherer and Nina Mast, Child Labor Laws are Under Attack in States Across the Country (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2023), available online.

3 U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division, “Child Labor,” accessed May 26, 2024, available online.

4 Administration for Children and Families, “Fact Sheet: Unaccompanied Children (UC) Program,” 2024, available online.

5 Three sponsor categories exist: (1) parent sponsor, (2) non-parent relative, and (3) unrelated adult. See the Office of Refugee Resettlement, “ORR Unaccompanied Children Program Policy Guide: Section 6,” updated February 27, 2025, available online for more on children’s placement and release from ORR.

6 Stephanie L. Canizales, Sin Padres, Ni Papeles: Unaccompanied Migrant Youth Coming of Age in the United States (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2024).

7 Alejandra Reyes-Velarde, “More Working Californians Slipped into Poverty as Pandemic Aid Expired, ” updated October 27, 2023, CalMatters, available online.

8 Latino Data Hub, “Individual Poverty Rate (<100% FPL) for Latinos, 2021,” accessed May 26, 2024, available online.

9 Taemin Ahn, Hector De Leon, Misael Galdámez, Ana Oaxaca, Rocio Perez, Denise Ramos-Vega, Lupe Renteria Salome, and Jie Zong, “15 Facts About Latino Well-being in California” (UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, June 2022), available online.

10 See Office of Refugee Resettlement, “ORR Unaccompanied Children Program Policy Guide: Section 6,” updated February 27, 2025, available online for more on eligibility and delivery of federal Post-Release Services.

11 Chiara Galli, Precarious Protections: Unaccompanied Minors Seeking Asylum in the United States (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2023).

12 Canizales, Sin Padres, Ni Papeles.; Sharon Tafolla, Andres Arias, Maria Escobar, and Meredith Van Natta, “Community Outreach Workers’ Perspectives on Public Charge: Impacts on Work and Immigrant Communities” (UC Merced Community and Labor Center, University of California Merced, Merced, March 2024), available online.

13 Immigrant Legal Resource Center, “Public Charge,” accessed 2025, available online.

14 Asad L. Asad, Engage and Evade: How Latino Immigrant Families Manage Surveillance in Everyday Life (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023).

15 Izaac Ornelas, Wenson Fung, Susan Gabbard, and Daniel Carroll, California Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) 2015-2019: A Demographic Employment Profile of California Farmworkers (JBS International Inc., 2022), available online.

16 Abigail F. Kolker and Maggie McCarty, Noncitizen Eligibility for Federal Housing Programs, (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2023), available online.

17 Ryan Allen, “The Relationship between Legal Status and Housing Cost Burden for Immigrants in the United States,” Housing Policy Debate 32, no. 3 (2022): 433-455.

18 Edward Orozco Flores, “Inequality at the Heart of California” (UC Merced Civic Capacity Research Initiative, University of California Merced, Merced, October 2019), available online.

19 Eric McGhee, Marisol Cuellar Mejia, and Hans Johnson, “California’s Renters,” (Public Policy Institute of California, San Francisco, February 2024), available online.

20 See Janine Nkosi, Amber R. Crowell, Patience Milrod, Veronica Garibay, and Ashley Werner, Evicted in Fresno: Facts for Housing Advocates (Stockton: Faith in the Valley, 2019), available online.

21 Torres Jr., Mauricio, “New Study: Undocumented Immigrants Contribute $8.5 Billion in California Taxes a Year” (California Budget and Policy Center, Sacramento, July 2024), available online.

22 Office of Refugee Resettlement, “Unaccompanied Alien Children released to Sponsors by County,” updated May 12, 2025. available online.

23 Berkeley Interdisciplinary Migration Initiative. N.d “Mapping Spatial Inequality,” n.d., available online.

24 Makinizi Hoover and Isabella Lucy, “The State of Housing in America” (U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Washington, March 2025), available online.

Disclaimer

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the University of California, Los Angeles, as a whole. The authors alone are responsible for the content of this report.

For More Information Contact:

Alberto Lammers, alammers@luskin.ucla.edu.