Implementation Lessons from the 2022 Medi-Cal Expansion to Undocumented Adults Aged Fifty and Above

Introduction

Undocumented immigrants are central to the nation’s economy and society, but they are too often excluded from public policies that ensure equitable access to health care. Approximately 11 million undocumented immigrants lived in the United States in 2019.1 In 2021, close to half (46 percent) of undocumented immigrants lacked health insurance coverage, compared to 25 percent of documented immigrants and 8 percent of US citizens.2 Consequently, undocumented immigrants had less access to high-quality health care when compared to documented immigrants and US citizens.3 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded access to health insurance, but mainly through Medicaid expansion and subsidies for state health insurance exchanges. Undocumented immigrants were ineligible for ACA coverage and were thus excluded from subsidized health insurance coverage.

California has the largest concentration of undocumented immigrant adults living in the United States at approximately 27 percent.4 An analysis of the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) from 2011 to 2018 provides an overview of the challenges that this population faces in the state.5

- Of all undocumented immigrants in California, 85.9 percent were Latino.

- The majority were low-income, with 46.1 percent having incomes that were 0–99 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) and 30.4 percent having incomes that were 100–199 percent of FPL.

- Most, 73.1 percent, spoke English “not well” or “not at all.”

- About a third, 33.0 percent, reported “fair/poor” health, compared to 16.5 percent of US-born citizens.

- Of all undocumented immigrants, 44.6 percent were uninsured, compared to 21.8 percent of documented immigrants and 9.2 percent of US-born citizens.

- When asked about access to health care, sixty percent of undocumented immigrants reported having a usual source of care, compared to 75.7 percent of documented immigrants and 85.9 percent of US citizens.

In 2018, nearly a decade after the implementation of ACA, 3.7 million previously uninsured adults had gained coverage in California through Medi-Cal or Covered California, both were prescriptions included in the ACA.6 Undocumented immigrants, however, were excluded from coverage under the ACA and had very few options for health insurance.7 It is estimated that in 2018, approximately 2 million undocumented immigrants were excluded from ACA subsidized coverage8 and projections for 2022 estimated that over a million would still lack access to health coverage (Figure 1).9 Private health insurance, provided mainly by employers or relatives, is the main source of coverage for undocumented immigrants. In addition, undocumented immigrants can enroll in Emergency Medi-Cal, also known as restricted-scope Medi-Cal, which covers emergency and pregnancy-related services. They can also access care at Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and other community clinics and enroll in medical home programs such as My Health LA and Healthy San Francisco.10

Figure 1. Uninsured Californians Aged Zero to Sixty-four by Eligibility Group, 2022 Projections

Source: Dietz et al., “Undocumented Californians Projected to Remain the Largest Group of Uninsured in the State in 2022.”

Shifting Immigrant Demographics

The US and California health systems will soon face important challenges caused by shifting immigrant demographics. Before the 2000s, circular migration eased the healthcare demand since many aging immigrants returned to their home countries. Current immigrants, however, are more likely to settle in the United States. As a group, immigrants are also aging faster than US-born adults. In California, the share of foreign-born adults aged 45 to 54 years old grew by 66.2 percent from 2003 to 2019. By contrast, the share of US-born adults in the same age cohort declined by 13.6 percent (Figure 2).11

Figure 2. Cumulative Percent Change in the US-born and Foreign-born Populations in California, 2003–19

Source: LPPI analysis of data from the California Health and Interview Survey, 2003–19.

In 2019, approximately 70 percent of California’s undocumented adults older than forty-five years of age had lived in the United States for more than fifteen years.12 Undocumented immigrants are ineligible for Medicare enrollment regardless of contributions, and many aging documented immigrants will remain ineligible for Medicare because they need to account for at least ten years of Social Security contributions to benefit from this program.13 If present trends continue, the demand for more comprehensive health coverage from aging uninsured immigrants will continue to rise. Also at risk are documented immigrants who have not contributed to Social Security for at least a decade. Both of these immigrant populations would have to rely on health insurance options offered by state and local governments.14

Medi-Cal Expansion to Undocumented Immigrants

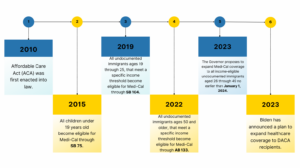

To address the needs of the state’s growing population of aging uninsured immigrants, the California legislature expanded full-scope Medi-Cal coverage to include undocumented immigrant adults (fifty years of age and older) beginning in May 2022. The initiative addresses federal restrictions on Medi-Cal funding and is financed with state funds.15 California expanded full-scope Medi-Cal coverage to all children (zero to eighteen years of age) in 2015, and another expansion in 2020 covers young adults (nineteen to twenty-five years old).16 A final expansion, this one for undocumented adults aged twenty-six to forty-nine, takes effect on January 1, 2024 (Figure 3, Table 1).17 With this expansion, all eligible adults, regardless of immigration status, can enroll in full-scope Medi-Cal.18

It is important to note that to circumvent federal restrictions, coverage for eligible undocumented immigrants continues to be financed through state funds. Eight other states, including Illinois, New York, Oregon, and Washington, have followed California’s lead by expanding Medicaid coverage to different segments of their eligible undocumented immigrant populations.19 In April 2023, President Joe Biden announced a plan to give Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients access to health care coverage through ACA prescriptions and Medicaid.20

Figure 3. Timeline of Medi-Cal Expansions for Undocumented Immigrants

Source: Compiled by the LPPI research team.

Table 1. Overview of Medi-Cal Expansions

Sources, compiled by the LPPI research team:

aDepartment of Health Care Services, “SB 75–Full Scope Medi-Cal Coverage for All Children.”

bDepartment of Health Care Services, “Do You Qualify for Medi-Cal Benefits?”

cDietz et al., California’s Biggest Coverage Expansion since the ACA.

dDepartment of Health Care Services, “Young Adult Expansion.”

eDepartment of Health Care Services, “Older Adult Expansion.”

fJohnson, “Estimated Cost of Expanding Full-Scope Medi-Cal.”

gDepartment of Health Care Services, “Ages 26 through 29 Adult Full Scope Medi-Cal Expansion.”

These government efforts are unequivocally important steps in the direction of universal health insurance coverage in California; however, it should be emphasized that this coverage option is only for eligible undocumented immigrants, meaning those with incomes that are 138 percent of FPL and below.21 Approximately 25 percent of undocumented immigrants in California were above this threshold.22 This income eligibility threshold excludes people with incomes above this limit from Medi-Cal enrollment, such as the self-employed and small business owners, and the high cost of living in much of California compounds the difficulties that these immigrants face. Their only feasible health insurance option is private insurance, which is unaffordable when purchased outside of Covered California or provided by an employer.

When uninsured undocumented immigrants above the Medi-Cal eligibility threshold are unable to afford private health insurance coverage, their only option is to deplete their assets to become Medi-Cal eligible, an option that goes against the goal of immigrant economic mobility. After the expansion of full-scope Medi-Cal coverage to eligible undocumented immigrants is fully implemented in 2024, new policy solutions will need to be proposed to cover the remaining share of undocumented immigrants—those who are not eligible for Medi-Cal coverage because their incomes are too high.

Goals of This Research

The first aim of this brief is to examine the short-term implementation lessons from the Medi-Cal expansion to adults aged fifty and over a year after its implementation to inform the planned expansion of full-scope Medi-Cal to adults twenty-six to forty-nine years of age in 2024. The second goal is to identify policy options to address undocumented immigrant adults aged fifty and over who will continue to be ineligible for Medi-Cal coverage because their incomes exceed the 138 percent FPL eligibility threshold.

Research Approach

We performed nine key informant interviews with representatives of community and government organizations that were involved in the 2022 expansion of full-scope Medi-Cal to adults aged fifty and older. To identify lessons that can be useful for the 2024 expansion, we used qualitative methods to identify the main facilitators and barriers that these organizations have encountered.

We used CHIS data from 2018 to 2020 to estimate the number of uninsured adults who were at least fifty years of age and had incomes at or above 139 percent of FPL during the study period. These Californians were ineligible for full-scope Medi-Cal. We also identify policy options for expanding coverage to this population through Covered California as an enrollment mechanism, following initial policy blueprints proposed in other states.

Implementation Lessons of the Medi-Cal Expansion to Adults Aged Fifty and Over

Using responses from our key informants, we identified three domains that provide lessons for the 2024 expansion of full-scope Medi-Cal: access to technology, language barriers, and immigration status.

Access to Technology

Governments and healthcare organizations increasingly rely on computers, information technology, and the internet to manage health insurance enrollment and maintain beneficiary coverage. Undocumented immigrants, however, disproportionately lack access to computers, mobile devices, or the internet, and this population is less likely to have digital literacy skills.23 This digital exclusion among immigrants was underlined during our conversations with enrollment assistants. Many highlighted their clients’ lack of access to computers, mobile devices, or the internet, which hindered the immigrants’ ability to begin the enrollment process for Medi-Cal. One enrollment assistant specifically mentioned having to create email accounts for the first time for many of their clients. Understanding the digital divide and developing alternative outreach methods for undocumented immigrants is a first consideration for community and government organizations involved in expanding Medi-Cal coverage.

Language Barriers

Approximately 52.1 percent of the US immigrant population reported limited English proficiency (LEP) in 2021.24 According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid households include a disproportionate share of adults with LEP, which makes it difficult for them to successfully secure and retain coverage even when they are eligible, since this language barrier makes it difficult for them to navigate bureaucratic hurdles.25 For instance, enrollees with LEP are five times more likely to lose coverage during the redetermination process than individuals without LEP.26 Even though the Medi-Cal application is available in over fifteen languages, our informants noted that many languages, including those spoken among Indigenous communities, are not represented. Our informants also highlighted the need for more translation services for eligible immigrants who speak Indigenous languages and for others who are not currently covered by Medi-Cal. Many local health departments and applicant services do not provide translation services for eligible immigrants. While the offering of materials in different languages is a strength of the Medi-Cal expansion, planning for the upcoming expansion should address the language barrier for the potential enrollees who are not fluent in any of the languages now accommodated by the program.

Immigration Status

A common barrier that many immigrants face, especially when accessing any type of social service, is the fear of being labeled as a public charge, which can make them ineligible for lawful permanent residence.27 In 2019, changes to the public charge rule made it difficult for immigrants to receive permanent residence status. These changes expanded the share of noncitizen immigrants who could be considered a public charge from 3 percent included in the 1999 policy to 47 percent for the duration of the rule.28 The Biden administration reversed these changes at the end of 2022; nevertheless, fear and misinformation persist among immigrants.

Previous research shows that the chilling effect of the changes in 2019 reduced the number of applications to Medicaid (and other public programs) among immigrants, including those who were eligible.29 Approximately 17 percent of noncitizen immigrants avoided public benefits enrollment in 2019 because of the changes. Research supported by LPPI shows that from 2016 through 2020, between 107,956 and 192,905 Latino immigrants and 1,294 and 4,702 Asian immigrants in California likely avoided Medicaid enrollment due to their fears about their immigration status.30

Even though the public charge rule has reverted to its original definition, confusion about the rule and fear of being considered a public charge continue to discourage enrollment into and use of public benefits, and some immigrants have disenrolled.31 Our informants reported that immigration status often discouraged immigrants who became eligible for full-scope Medi-Cal in spite of assurances that immigration data is confidential and that it is not shared with immigration authorities. Planning for the 2024 Medi-Cal expansion should include more persuasive ways of assuring potential enrollees about the confidentiality of personal data and highlighting the benefits of Medi-Cal coverage when compared to the risks of remaining uninsured.

Policy Options to Expand Coverage to Adults Aged Fifty and Above Who Remain Ineligible for Medi-Cal Coverage

A study undertaken for the California Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) in 2021 projected that approximately 235,000 adults older than fifty years of age would gain health coverage through full-scope Medi-Cal on an ongoing basis after 2022. Most of these undocumented immigrants would have been previously enrolled in Emergency Medi-Cal.32

To estimate the number of undocumented immigrant adults aged fifty and older who would remain ineligible to enroll in Medi-Cal because their income exceeds the eligibility threshold of 138 percent of FPL, we pooled data from the California Health Interview Survey from 2018 to 2020. In Table 2, we show the number and percentage of these adults by insurance eligibility and income level for 2020. Approximately 141,557 immigrants without permanent residence in California reported household incomes above 138 percent of FPL, and close to half of this population was uninsured (46.0 percent The remaining 54.0 percent reported some type of health coverage, either through emergency Medi-Cal (11.5 percent), employer-based insurance (30.2 percent), or privately purchased insurance (6.2 percent), or they had access to local programs such as My Health LA or Healthy San Francisco (6.1 percent). Based on our estimations, approximately 65,180 uninsured undocumented adults aged fifty and older will be left out of the expansion because their incomes exceed the Medi-Cal income threshold.

Table 2. Adults in California Aged Fifty and Above without a Green Card, by Insurance Type and Income Level, 2020

Source: LPPI analysis of California Health Interview Survey, 2018–2020.

Notes: Percentages refer to proportions within an income group. FPL = federal poverty level; n/a = masked due to small number of respondents; 0 (0%) = no respondents. Not all columns total 100% due to masked cells from small sample sizes. The sample excludes a minimal fraction of individuals enrolled in Medicare and subsidized participation in Covered California.

Recommendations

Based on our key informant interviews and our analyses of CHIS data, we recommend the following policy actions:

- Implementation of the recently approved expansion of Medi-Cal eligibility to all low-income residents regardless of immigration status, as this would result in approximately 698,000 individuals between the ages of twenty-six and forty-nine gaining health care coverage.

- Address the technological, linguistic, and immigration barriers that eligible immigrants face when attempting to enroll or renew Medi-Cal coverage through government and community-based partnerships.

- Allow undocumented immigrants with incomes above 138 percent of FPL to purchase subsidized health coverage through Covered California, using state funds when federal regulations prohibit the use of federal funds.

The states of Colorado and Washington have recently implemented policies to expand health coverage access for undocumented individuals who do not meet Medicaid’s income threshold. Through a legislative measure passed in 2021, Colorado created a program, OnmiSalud, which uses state funds to provide health insurance options to immigrants with incomes below 150 percent of FPL. Those who earn more can buy insurance through the state’s exchange, but at full price.33 In 2022, Washington obtained approval for a State Innovation Waiver, or section 1332 waiver, from the US Department of Health and Human Services that would allow the provision of subsidies for undocumented immigrants living in the state who earn between 139 percent and 250 percent of FPL.34 This waiver is the first of its kind to waive Section 1312(f)(3) of the ACA which bars undocumented immigrants from enrolling in the ACA.35 State funds will be used to provide subsidies to these undocumented immigrants.36

In California, a bill introduced in December 2022, Assembly Bill 4, is intended to remove immigration status as a barrier to enrolling in health care coverage. The current form of the bill would direct Covered California to develop options for expanding access to affordable health care coverage to Californians regardless of immigration status by February 2024.37

Future legislative efforts to close the coverage gap

The state funding needed to expand coverage to undocumented immigrants above the Medi-Cal threshold might be limited due to the budget deficit forecasted for California for the 2023-24 fiscal year. In this case, future expansions could accommodate to different age cohorts as funding become available. A first step could be to expand coverage to the approximately 65,180 undocumented immigrants aged fifty and above who will not be eligible to enroll in Medi-Cal because their income exceeds the Medi-Cal eligibility threshold.

Footnotes

1 Migration Policy Institute, “Profile of the Unauthorized Population: United States,” accessed May 25, 2023, available online.

2 Kaiser Family Foundation, “Health Coverage and Care of Immigrants,” KFF website, updated March 30, 2023, available online.

3 Alexander Ortega, Ryan McKenna, Jessie Kemmick Pintor, Brent Langellier, Dylan Roby, Nadereh Pourat, Arturo Vargas Bustamante, and Steven Wallace, “Health Care Access and Physical and Behavioral Health among Undocumented Latinos in California,” Medical Care 56, no. 11 (2018): 919–26, available online.

4 Findings reported here from the LPPI analysis of CHIS data, 2011–18, were published in Arturo Vargas Bustamante, Jie Chen, Lucía Félix-Beltrán, and Alexander N. Ortega, “Health Policy Challenges Posed by Shifting Demographics and Health Trends among Immigrants to the United States,” Health Affairs 40, no. 7 (2021): 1023–1176.

5 Ibid.

6 Anne Sunderland, “Ten Years After: The ACA’s Success in Five Charts,” CHCF Blog, March 17, 2020, available online.

7 Paulette Cha and Shannon McConville, Public Policy Institute of California, Health Coverage and Care for Undocumented Immigrants: An Update, 2021 (San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California, 2021), available online.

8 Insure the Uninsured Project, “ITUP Snapshot: Remaining Uninsured in California,” revised December 2019, available online.

9 Miranda Dietz, Laurel Lucia, Srikanth Kadiyala, Tynan Challenor, Annie Rak, Dylan H. Roby, and Gerald F. Kominski, “Undocumented Californians Projected to Remain the Largest Group of Uninsured in the State in 2022,” UC Berkeley Labor Center blog, April 13, 2021, available online.

10 Arturo Vargas Bustamante and Lucia Félix-Beltrán. "How to expand health care coverage to undocumented immigrants: a policy toolkit for state and local governments." (Berkeley: UC California Initiative for Health Equity and Action. 2020 Jan), available online.

11 LPPI analysis of data from the California Health and Interview Survey, 2003–19.

12 Authors’ analysis of pooled data from the California Health Interview Survey, 2011–19.

13 Vargas Bustamante and Félix-Beltrán, “How to expand health care coverage to undocumented immigrants: a policy toolkit for state and local governments.”

14 Arturo Vargas Bustamante, Jie Chen, Lucía Félix-Beltrán, and Alexander N. Ortega, “Health Policy Challenges Posed by Shifting Demographics and Health Trends among Immigrants to the United States,” Health Affairs 40, no. 7 (2021): 1023–1176.

15 Department of Health Care Services, “Older Adult Expansion,” updated March 20, 2023, available online. See also John Cannan, “A Legislative History of the Affordable Care Act: How Legislative Procedure Shapes Legislative History,” Law Library Journal 105, no. 2 (2013): 131–74.

16 Department of Health Care Services, “SB 75—Full Scope Medi-Cal for All Children,” updated March 23, 2021, available online; and Department of Health Care Services, “Young Adult Expansion,” Department of Health Care Services, updated November 15, 2022, available online.

17 Department of Health Care Services, “Ages 26 through 49 Adult Full Scope Medi-Cal Expansion,” updated December 20, 2022, available online.

18 Miranda Dietz, Laurel Lucia, Srikanth Kadiyala, Tynan Challenor, Annie Rak, Dylan Roby, and Gerald Kominski, California’s Biggest Coverage Expansion since the ACA: Extending Medi-Cal to All Low-Income Adults (Berkeley: UC Berkeley Labor Center, 2022), available online.

19 Arturo Vargas Bustamante, Joseph Nwadiuko, and Alexander Ortega, “State-Level Legislation during the COVID-19 Pandemic to Offset the Exclusion of Undocumented Immigrants from Federal Relief Efforts,” American Journal of Public Health 112, no. 12 (2022): 1729–31.

20 White House, “Fact Sheet: President Biden Announces Plan to Expand Health Coverage to DACA Recipients,” April 13, 2023, available online.

21 Department of Health Care Services, “Do You Qualify for Medi-Cal Benefits?,” updated February 21, 2023, available online.

22 Arturo Vargas Bustamante, Jie Chen, Lucía Félix Beltrán, and Alexander N. Ortega, “Health Policy Challenges Posed By Shifting Demographics And Health Trends Among Immigrants To The United States,” Health Affairs 40, no. 7 (July 2021): 1023-1176.

23 Abby Outterson, “Digital Exclusion and the Undocumented,” Public Health Post, October 13, 2022, available online.

24 Migration Policy Institute, “California: Language and Education,” available online.

25 Kaiser Family Foundation, “Unwinding of the PHE: Maintaining Medicaid for People with Limited English Proficiency,” KFF website, updated March 3, 2022, available online.

26 Mansha Mirza, Elizabeth Adare Harrison, Luvia Quiñones, and Hajwa Kim, “Medicaid Redetermination and Renewal Experiences of Limited English Proficient Beneficiaries in Illinois,” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 24 (February 2022): 145–53.

27 Arturo Vargas Bustamante, Lucia Félix-Beltrán, Joseph Nwadiuko, and Alexander N. Ortega, “Avoiding Medicaid Enrollment after the Reversal of the Changes in the Public Charge Rule among Latino and Asian Immigrants,” Health Service Research 57, no. S2 (2022): 195–203.

28 Migration Policy Institute, “Chilling Effects: The Expected Public Charge Rule and Its Impact on Legal Immigrant Families’ Public Benefits Use,” June 2018, available online.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Mirza et al., “Medicaid Redetermination and Renewal.”

32 Ben Johnson, “Estimated Cost of Expanding Full‑Scope Medi‑Cal Coverage to All Otherwise‑Eligible Californians Regardless of Immigration Status,” Legislative Analyst’s Office website, May 5, 2021, available online.

33 Connect for Health Colorado, “OmniSalud,” accessed June 13, 2023, available online.

34 Elizabeth Hovde, “Washington State Has Permission to Subsidize Health Insurance for Undocumented Immigrants,” Washington Policy Center website, December 12, 2022, available online.

35 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Washington: State Innovation Waiver”(Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Baltimore, December 9, 2022), available online.

36 Ibid.

37 The status of Assembly Bill 4 is tracked on the LegiScan website, available online.