All Work and No Pay: Unpaid Latina Care Work During the Covid-19 Pandemic

Executive Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has left no facet of life untouched, upending norms and exacerbating inequalities. Latinas, who often lacked the wealth and education to weather economic shocks1 and were primarily responsible for household care in their families,2 bore the brunt of pandemic-induced job losses. In 2019, the number of Latinas in the U.S. labor force was projected to grow by 25.8% over the next decade—nearly nine times the projected growth of white women in the labor force (3.1%).3 However, at the pandemic shutdown’s height in April 2020, one of five Latinas were unemployed, a larger share than that of any other demographic group.4 Many Latinas left the workforce altogether to care for children in the face of school and daycare closures.5

By some estimates, the annual economic value of all women’s unpaid care work in the United States equals $1.5 trillion.6 And beyond their economic importance, domestic work and caregiving stand as the foundation of society, building up the next generation and giving workers a place of reprieve.7 Family caretaking helps maintain a stable home that can provide a sense of belonging for all household members.8 Family caretakers include the abuelitas (grandmothers) who watch their grandchildren and empower working parents, as well as the mothers who guide their children through math problems and enable them to succeed in school.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and into the recovery, questions about the well-being of the Latina workforce have remained: How uneven was the division of household work between Latinos and Latinas during the pandemic? To what degree were existing household divisions of labor exacerbated or alleviated as the pandemic raged on? Further, have Latinas returned to work outside the home at pre-pandemic levels, or did the pandemic deepen preexisting workforce inequalities?

This report attempts to answer these questions using publicly available American Time Use Survey (ATUS) microdata to analyze how daily time spent on household care work changed for Latinas throughout the pandemic relative to Latino men and other women.9 Additionally, it uses data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey to determine whether caregiving responsibilities continue to affect Latinas’ paid employment.

Our main findings are:

- In 2020, Latinas spent quadruple the time caring for their families and double the time maintaining their household compared to Latino men. Whereas Latinas spent more than one hour per day caring for household members, Latinos averaged just .2 hours. Latinas also spent 2.8 hours a day maintaining their homes, compared to 1.5 hours for Latinos.10 As of 2021, Latina family care time had returned to pre-pandemic levels but remained roughly double that of Latinos (0.7 hours versus 0.3 hours, respectively). Latinas also spent more time caring for their households in 2021 than Latino men (2.7 hours versus 1.2 hours for Latinos).

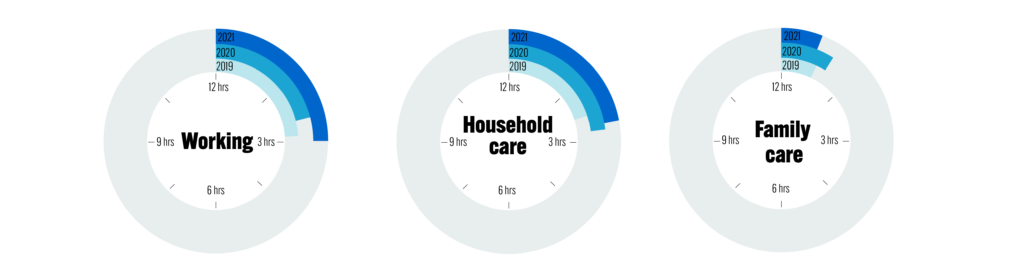

- Compared to 2019, in 2020 Latinas spent less time working for pay and more time caring for their households or household members. In 2020, Latinas spent 8% less time on paid work-related activities than in 2019, but 30% more time caring for family members and 18% more time on household activities (see Figure 1). In 2021, Latinas’ paid work time surpassed pre-pandemic levels (3.0 hours), but their time spent on household activities increased by more than 10% compared to 2019 (from 2.4 hours to 2.7 hours).

Figure 1: Average Time Spent by Latinas on Work, Household Care, and Family Care, 2019-21

Source: LPPI analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata (2018-2021), available online.

Notes: * 2020 data reflects time use from May 10 to December 31, 2020.

- Immigrant Latinas and Latinas without a college degree experienced larger changes in time spent caring for their families than their native-born and college-educated peers. In 2020, immigrant Latinas spent 24% less time working than in 2019 (vs. +7% for native-born Latinas) and 44% more time caring for household members (+14% for native-born Latinas). Similarly, high school-educated Latinas spent 5% less time working in 2020 than in 2019 (-5% for college-educated Latinas) and 71% more time caring for family members (+29% for college-educated Latinas) than in 2019.

- As of August 2022, 1.4 million Latinas were not working due to family care responsibilities—nearly the same number as in August 2020.11 This number has remained virtually unchanged over the past two years. Early into the COVID-19 pandemic (August 2020), 1.5 million Latinas were already not formally working due to child or elderly care demands. Throughout the pandemic, Latinas were more likely than women overall to stop working due to child and elder care needs.

Based on our findings, we recommend the following policy actions:

- Help working Latinas re-enter the workforce and maintain stable employment by:

- Providing child care subsidies and improving child care quality, affordability, and availability. States and the federal government should improve access to affordable and subsidized child care. Investments in child care subsidies and supply would prevent Latinas from having to choose between their work and their family and encourage their re-entry into the labor force.

- Permanently expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). For low-wage Latinas, the EITC provides an extra incentive to work and the funding to make work feasible. The American Rescue Plan temporarily widened eligibility to include workers of various ages and workers without children. Congress should make these changes permanent—adding workers with individual taxpayer numbers (ITINs)—and pair them with funding for Spanish-language outreach.

- Strengthening education and training programs to up-skill Latinas. Access to high-quality, stable employment begins with education. Federal and state governments should fund financial assistance and K-12 pipeline programs to improve Latina college admission and completion rates. Colleges and universities should also establish transfer pathways from community colleges to four-year universities, support returning students with financial aid and priority registration, and help student-parents through targeted advising, increased financial aid, and subsidized child care.

- Provide support and flexibility for Latinas and their families when caretaking needs arise by:

- Establishing federal and state paid family and medical leave programs. In moments of crisis or unforeseen change, paid family and medical leave benefits would allow Latinas to take time off while maintaining their incomes and jobs. Congress should act to create a paid family and medical leave program, as proposed in the Build Back Better Act. In the absence of federal action, state legislatures should develop their own programs, as California has.

- Compensating unpaid caregivers. Latinas who choose or need to remain at home to care for their families should receive some form of compensation for their household work, as they do in peer countries. Funding for unpaid caregivers could take the form of Social Security credits, a new tax credit, or reforming unemployment insurance to include part-time caregivers.

Latinas are the backbones of their families, having supported their households during an unprecedented global pandemic. They should be able to support their families without risking their career, financial stability, or future. To achieve an equitable economic recovery, we must build the social infrastructure to prevent workers from facing costly work-family decisions, create high-quality and flexible jobs, and compensate unpaid caregivers for the value their familial and household labor generates.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many Latinas to make difficult decisions, often between paid work or family care. Before the pandemic, Latina mothers were more likely than others to stay at home with their children due, in part, to cultural beliefs about raising children.12 Latinas also bore a larger share of pre-pandemic household responsibilities than Latinos,13 spending 3.5 hours more than Latino men on unpaid household and care-related work.14 They were also more likely to care for aging relatives than Latino men15 and reported that they often adjusted their work schedules or took time off to care for elderly family members.16

As previous LPPI research noted, the pandemic deepened the unequal distribution of domestic work. Latinas experienced sharp job losses17 given that many held jobs in the industries hit hardest by the pandemic, such as leisure and hospitality.18 These vulnerable industries also provided the least flexibility for telecommuting.19 Many could not find or return to work due to their responsibility to care for school-aged children or elderly parents.20 Consequently, more Latinas left the workforce during the pandemic than any other demographic group. In July 2022, the Latina labor force participation rate was 3.7 percentage points lower than in February 2019 (see Figure 2).21

Figure 2: Percentage-point Change in Labor Force Participation Rate (July 2021 and 2022 versus February 2019)

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Situation News Release,” Tables A-2 and A-3, with monthly archives available online.

Notes: Data depict seasonally adjusted values for individuals 20 years of age and older. The BLS does not disaggregate employment data by gender for Asian Americans in its monthly jobs report. Additionally, it does not aggregate Pacific Islanders with Asian Americans. February 2019 was chosen to highlight pre-pandemic labor force participation levels.

These issues compounded because Latino households—which tend to have younger children—were more exposed to the closures of child care centers than Black or white households22 and experienced more child care disruptions than white households.23 Though school reopenings granted a reprieve and a return to work for many women,24 heavily Latino and Black school districts were slower to reopen and less likely to offer in-person instruction than districts with more white students.25

Many Latino households, left without any other recourse, reported that a household member quit, lost a job,26 or took unpaid leave to care for children.27 More often than not, when Latino households faced these decisions, Latinas were forced to leave the labor force to manage collective home responsibilities.

By some estimates, the annual economic value of all women’s unpaid care work in the United States equals $1.5 trillion.28 And beyond their economic importance, domestic work and caregiving together form the foundation of society, building up the next generation and giving workers a place of reprieve.29 Family caretaking helps maintain a stable home that can provide a sense of belonging for all household members. Family caretakers include the abuelitas (grandmothers) who watch their grandchildren and empower working parents, as well as the mothers who guide their children through math problems and enable them to succeed in school.

However, it is still unclear how household work and caregiving disparities between Latinas and Latinos evolved during the pandemic. A March 2021 survey found that Latina mothers were more likely than Latino fathers (30% versus 16%) to rate pandemic child care responsibilities as “very difficult.”30 However, the differences in time spent caring for family members and their impacts on Latina employment have yet to be quantified. This report fills the research gap by estimating the time Latinas spent on these responsibilities and the employment effects of foregoing paid work for unpaid care work on Latinas.

Methodology

Using American Time Use Survey (ATUS) microdata, we analyzed the evolution of daily time spent on household care work for Latinas from 2018 to 2021 relative to Latino men and other women.31 The ATUS, accessed via IPUMS,32 is a nationally representative survey that measures how people split their time between life’s activities. We look at time spent working, caring for household members (e.g., children or other adults), and household activities (e.g., house cleaning, cooking, and home repairs).33 Time-use statistics presented below were weighted and cross-tabulated to create individual-level data by race and gender for 2018 to 2021.34 We include 2018 data as a secondary point of reference for pre-pandemic trends.

While data for 2018, 2019, and 2021 capture the entire calendar year, the COVID-19 pandemic affected data collection for 2020. The Census Bureau did not collect data between March 18 and May 9, 2020, out of concern for staff safety, but resumed operations in mid-May. As a result, ATUS data for 2020 do not include any observations between March 17 and May 9.

Considering these challenges, we followed IPUMS guidance and limited our 2020 data to observations recorded between May 10 and December 31, 2020. This restriction allowed us to isolate the impact of the pandemic on time use, by comparing data from 2019 to this period in 2020.35 More importantly for our analysis, we did not have data for April 2020, when the entire country was encouraged to stay home and child and domestic care responsibilities were at their peak.

In addition to analyzing ATUS data, this report also uses the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey to determine whether caregiving responsibilities continue to affect Latinas’ paid employment in 2022. The Household Pulse Survey is an experimental, high-frequency survey that tracks the social and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. households.36 The microdata—accessed via the Urban Institute’s data catalog37—were cross-tabulated weekly by race and gender.38 This dataset covers August 2020 to June 2022 (survey phases 2, 3, and 3.1 to 3.5), allowing a glimpse at the months since the latest available ATUS data.39

Using the Household Pulse Survey, we first analyzed the share of Latinas not currently working due to elder or child care responsibilities. Then, we used the new child care questions beginning on April 14, 2021 (phase 3.1) to quantify the number of Latinas impacted by child care closures and whether they continued to work at their pre-pandemic capacity.

Findings

How Latinas’ time use changed throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, 2019 – 2021

(Analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata)

Time Spent Working

In 2020, a year unlike any other, Latinas spent less time working for pay and more time caring for their households or household members (see Figure 3). On average, Latinas spent just 2.6 hours each day on work-related activities, down 7.8% compared to 2019, according to ATUS data.

Except for Black men, all other workers also spent less time working in 2020 compared to 2019. Overall, Black women saw the greatest decrease in daily work time (-20%), dropping from 2.9 daily hours on work-related activities in 2019 to 2.6 hours in 2020. Latinos experienced the second largest reduction in daily work time (-18.6%).

In 2021, most groups worked at similar rates as before the pandemic. Latinas and Latinos, for instance, worked roughly the same number of hours in 2021 as they did in 2019. In comparison, white men and women decreased their working time between 2019 and 2021 (-6.4% and -4.9%, respectively). Black men were the only group of men who increased their working time between 2019 and 2021 (+15.1%).

Figure 3: Average Hours per Day Spent on Work-Related Activities by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender, 2018-21

Source: LPPI analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata (2018-21), available online.

Notes: * 2020 data reflects time use from May 10 to December 31, 2020.

The gender gap in time spent working

The COVID-19 pandemic also exacerbated preexisting gender disparities in time spent working. Before the pandemic, Latinas, white women, and Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) women spent just 2.9 hours on average each day on work-related activities, while Black women spent 3.2 hours (see Figure 3). All groups of men spent upwards of 3.7 daily hours working in 2019, and between 0.5 to 2.1 daily hours more than women working (see Table 1). The largest gender gap, however, was between Latinos and Latinas: Latinos spent 2.1 daily hours more than Latinas on work in 2019.

Throughout the pandemic, the working-time gap between Latinos and Latinas remained higher than those of all other groups but decreased from pre-pandemic levels. Latinos worked 2.1 more daily hours than Latinas in 2019, 1.4 more hours in 2020, and 1.7 more hours in 2021. In contrast, Black men and women saw an increase in this gender gap. While Black men spent only .5 hours more on work than Black women in 2019, that gap grew to 1.3 hours in 2020 and 1.2 hours in 2021.

Table 1: Gender Gaps in Time Spent Working by Race and Ethnicity, 2019-21

Source: LPPI analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata (2018-21), available online.

Notes: * 2020 data reflects time use from May 10 to December 31, 2020.

Time spent on family care

In 2020, Latinas also spent more time feeding infants, helping school-aged children with online learning, and caring for the health needs of household adults—among additional caregiving activities—than any other demographic group (see Figure 4). On average, Latinas spent more than one hour each day caring for family members in 2020, an increase of 29.7% from the year before. Conversely, Latino men spent .2 hours each day caring for household members in 2020, five times less than Latinas. For Latino men, this also marks a 25.3% decrease in time spent caregiving from 2019.

Turning to other groups, AAPI women were the only other group of women to increase their time spent caregiving, spending 14.9% more time in 2020 (1 hour) compared to 2019 (.9 hours). Black men were the only male group to increase their time spent caregiving from 2019 to 2020, spending an average of .3 hours daily on caregiving in 2019 and .4 hours by 2020, a 33% rise. In addition to Latinos, most other groups saw a decrease in time spent caregiving over the same time period: white men decreased time spent on caregiving by 20.3%, Black women by 12%, and white women by 8.9%.

Figure 4: Average Hours per Day Spent Caring for Household Members by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender, 2018-21

Source: LPPI analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata (2018-21), available online.

Notes: Time spent caring for household members refers to time individuals spend on activities to care for any adult or child in their household, such as providing physical, medical, or personal care.

* 2020 data reflects time use from May 10 to December 31, 2020.

The gender gap in time spent caring for household members

Gender-based differences in care responsibilities remained constant even as time use returned to pre-pandemic levels. In 2019, all groups of women spent more time caring for household members than men, though Latinas—who spent .5 hours daily on caregiving than Latinos—felt a particularly large divide (see Table 2). In 2020, the gender gap between Latinas and Latinos grew to 0.8 hours. This gender gap, combined with the working-time gender gap discussed previously, suggests that Latinas were left to care for their families and homes at the expense of their careers. By 2021, the gender gap in caregiving time dropped to 0.4 hours.

Meanwhile, compared to their male counterparts, in 2019 AAPI and Black women spent just 0.4 hours more on family care, and white women 0.3 hours more. In 2020, this gender gap decreased slightly by 0.1 hours for white and Black women but grew by the same amount for AAPI women. By 2021, the gender gap in time spent on family care was smallest for AAPI women, who spent just 0.1 hours more caregiving per day than AAPI men.

Table 2: Gender Gaps in Time Spent on Family Care by Race and Ethnicity, 2019-21

Source: LPPI analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata (2018-21), available online.

Notes: * 2020 data reflects time use from May 10 to December 31, 2020.

Time spent on household activities

Domestic work, including cleaning, cooking, and other household activities, also took up more of Latinas’ time in 2020 than in the previous year. On average, Latinas spent 2.8 hours daily on household work in 2020—up 17.5% from 2019 (see Figure 5) and more than any other group. Latino men also spent 34.7% more time on household activities in 2020 than in 2019, but Latinas still spent almost double the time. For comparison, AAPI women had the largest increase in time spent on household care among all groups (+38.8%)—increasing from 1.9 hours in 2019 to 2.7 hours in 2020—while Black women saw the smallest increase (+5.9%), 1.6 hours in 2019 to 1.7 hours in 2020.

By 2021, Latinas’ household work responsibilities had not decreased. Latinas spent 10.3% more time managing their households in 2021 (2.7 hours) than in 2019 (2.4 hours) despite also experiencing a 3.4% increase in their time spent working for pay over the same period (2.9 hours in 2019 to 3 hours in 2021, see Figure 3).

Figure 5: Average Hours per Day Spent on Household Work Activities by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender, 2018-2021

Source: LPPI analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata (2018-21), available online.

Notes: Household activities refer to the time individuals spend maintaining their households, including (but not limited to) housework, cooking, yard and pet care, vehicle maintenance, and repair and home maintenance.

*2020 data reflects time use from May 10 to December 31, 2020.

The gender gap in time spent on household work

Racial and ethnic differences in the gender gap in time spent on household work remained relatively unchanged during the pandemic. Since 2019, for instance, Latinas and Latinos have had the largest disparity in time spent on household work. In 2019, Latinas spent 1.3 more hours than Latinos on the household, which steadily increased to 1.5 hours in 2021 (see Table 3). The gender gap between Black women and men, on the other hand, remained relatively stable at the height of the pandemic but increased from .5 hours in 2020 to .7 hours in 2021, due to a 36% decline in time spent on household work by Black men (see Figure 5).

AAPI men and women had the largest variance in time spent on household work. While AAPI women spent 0.8 hours more than their male counterparts on household work in 2019, the gap grew to 1.5 hours in 2020. By 2021, the gender gap between AAPI men and women decreased to 0.7 hours. Between 2020 and 2021, AAPI women decreased their time spent on household work by 18.2% (see Figure 5) and increased their time spent working for pay by 27.2% (see Figure 3). Thus, as AAPI women returned to work, they redistributed the burden of household responsibilities with their male counterparts.

Table 3: Gender Gaps in Time Spent on Household Work by Race and Ethnicity, 2019-21

Source: LPPI analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata (2018-21), available online.

Notes: * 2020 data reflects time use from May 10 to December 31, 2020.

Why Latina outcomes may have differed

As demonstrated above, the pandemic disproportionately affected Latinas’ ability to work and increased their household responsibilities. One reason for this differential impact may be family composition. Compared to other women, Latinas are younger and more likely to have a child under five (see Appendix Table A). In 2020, for instance, 21.3% of Latinas had a child under five, compared to just 9.8% of white women. Latinas were also more likely to have a child of any age in the household: more than half (59.8%) of Latinas had a child at home in 2020, compared to 31.5% of white women.

Additionally, Latinas often lacked access to high-quality jobs that afforded them the ability to work from home. Pre-pandemic, few Latinas had completed a college degree (19.4% in 2019; see Appendix Table A). As a result, Latinas were overrepresented in low-wage, pandemic-vulnerable industries requiring in-person presence—for instance, retail trade (12.4% of employed Latinas in 2019; Appendix Table B) and accommodation and food services (14.2%)—and were less likely to work in industries that translated to a remote work environment like food service or retail trade.40 Consequently, in both 2020 and 2021, Latinas were the least likely group of women to have worked remotely (see Figure 6). In the absence of child care for small children and lack of job flexibility, many Latinas left the workforce altogether.

Figure 6: Telework Rates for Employed Women by Race and Ethnicity

Source: LPPI analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata (2020-21), available online.

Notes: * 2020 data reflects time use from May 10 to December 31, 2020.

SPOTLIGHT: How Latina time use differed by nativity and educational attainment

Not all Latinas experienced the pandemic’s effects on household and care work equally. Latinas with a high school degree or less experienced the most significant increase in time spent on domestic and family care work (see Table 4). Compared to 2019, in 2020 high school-educated Latinas spent 71% more time caring for family members and 15% more time on household work. In contrast, Latinas with a college education spent roughly the same amounts of time on paid and household labor in 2019 and 2020. However, college-educated Latinas spent 29% more time caring for household members than a year prior—likely due to the absence of childcare options during the pandemic.

Looking at nativity, immigrant Latinas spent the most time on household labor and experienced the greatest decrease in time spent working for pay in 2020. On average, foreign-born Latinas spent 1.3 hours per day caring for household members and 3.2 hours maintaining their households. At the same time, their time spent on paid work fell to 2.4 hours (-19%). In contrast, native-born Latinas spent .8 hours per day caring for household members in 2020 and 2.3 hours per day on household activities. Native-born Latinas also spent more time on paid work in 2020 than foreign-born Latinas.

Most Latinas, regardless of education and nativity, saw their daily time spent on work return to or surpass pre-pandemic levels by 2021, with a few exceptions. First, immigrant Latinas continued to bear the brunt of household responsibilities at the expense of paid work. Whereas native-born Latinas spent 18% more time working in 2021 than in 2019, foreign-born Latinas spent 7% less time on paid work in 2021. Moreover, their domestic work responsibilities remained elevated in 2021. Second, Latinas with a high school degree or less worked half an hour more daily than in 2019, but they also continued to spend more time working in the household.

Table 4: Average Hours per Day Spent on Selected Activities for Latinas by Education and Nativity, 2019-21

Source: LPPI analysis of American Time Use Survey microdata (2018-21), available online.

Notes: * 2020 data reflects time use from May 10 to December 31, 2020.

Together, these facts may suggest a segmentation of household work norms: Latinas with college degrees and U.S.-born Latinas are less likely to carry the brunt of domestic work responsibilities. In contrast, immigrant Latinas and those with less education may be expected to provide most of the household care.

On the other hand, the data also point to the unequal work outcomes faced by vulnerable workers: those with a high school education or less41 and immigrant women42 experienced higher unemployment rates than other workers. While many college-educated Latinas held remote work-friendly jobs, Latinas with lower educational attainment and foreign-born Latinas were overrepresented in the low-wage industries—for instance, service and hospitality—that suffered the greatest job losses.43

How family care responsibilities have kept Latinas out of the workforce

(Analysis of U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey microdata)

Data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey show that child and elder care responsibilities continue to affect Latina work outcomes in 2022 (see Figure 7). At the end of August 2020 (Week 13 in the survey), 1.5 million Latinas were not working for pay or profit because they were caring for family members. Two years later, this number was relatively unchanged. As of early August 2022 (Week 48), 1.45 million Latinas were not working due to family care responsibilities. In contrast, relatively few Latinos at either point in time were caring for children or elders instead of working for pay.

The Household Pulse data also confirm our findings from the ATUS: family care responsibilities impacted Latinas more than other women. In end-August 2020 (Week 13), 16.2% of Latina women were not working for pay due to care responsibilities, compared to just 11.3% of all women. This disparity remained in early August 2022 (Week 48)—15.9% of Latinas were not working compared to 11% of all women. Thus, Latinas have been more likely to eschew paid labor to care for their families than other groups at each point of the pandemic and recovery.

Figure 7: Share of Adults Not Formally Working Due to Care Responsibilities by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender

Source: LPPI analysis of Household Pulse Survey microdata (Weeks 13-48), available online.

Notes: Adults are classified as "not working" if they answered no to the question, "In the last seven days, did you do any work for either pay or profit?" Further, adults are classified as having care responsibilities if they noted that they did not work because they were caring for children not in school or daycare or for an elderly person. In contrast to Phase 1, later survey phases have used two-week collection and dissemination periods. Despite going from a one- to a two-week collection period, the Household Pulse Survey calls these collection periods "weeks" to maintain continuity with Phase 1. Phase 3.3 and onward have also shifted to a two-weeks-on, two-weeks-off collection approach, reflected in the gaps between dates.

In April 2021, the Household Pulse Survey also began to ask about child care access for children ages 11 or younger and the subsequent impact of any disruptions. While the above analysis focused on women caring for children and elders, most women did not work for pay due to child care responsibilities.

On average, 1.4 million Latinas were impacted by child care closures, unavailability, and unaffordability each week.44 While the Household Pulse Survey data can vary significantly week-to-week, Latinas were more likely to supervise their children earlier in the pandemic in response to child care issues. However, as the pandemic and its recovery have continued, Latinas were more likely to take paid leave, cut their hours, or leave a job altogether.

Figure 8: Latinas’ Responses to Child Care Disruptions, Percent of Impacted Latinas

Source: LPPI analysis of Household Pulse Survey microdata (Weeks 13-48), available online.

Note: Respondents were allowed to make multiple selections, so categories are not mutually exclusive. Totals will not add up to 100%.

Further, Latinas have been more likely to leave a job altogether in response to child care disruptions than other women (see Figure 9). As of August 2022, 31.8% of Latinas had left a job due to child care challenges compared to 20.6% of women overall. On the other hand, Latinas were less likely to take paid leave compared to other women.

Figure 9: Women who Left a Job or Took Paid Leave Due to Childcare Disruptions, Percent of Total Impacted Group

Source: LPPI analysis of Household Pulse Survey microdata (Weeks 13-48), available online.

Note: Respondents were allowed to make multiple selections, so categories are not mutually exclusive. Totals will not add up to 100%.

Policy Recommendations

Our analysis emphasizes the precarity of Latina employment in the United States. Latinas are expected to manage their households, care for their families, and work for pay, all while lacking the resources like education or child care, to manage daily responsibilities without risking their careers. Segregation into low-wage, vulnerable jobs has also left many Latinas without financial resources or career progression opportunities.45 As the pandemic has dragged on, many Latinas have left their jobs or turned to part-time work,46 highlighting a need for policies that “make it easier to be a working Latina.”47

Based on our findings, we recommend the following policy actions:

- Help working Latinas and women re-enter the workforce and maintain stable employment.

- Provide child care subsidies and improve child care quality, affordability, and availability. The Household Pulse Survey data show that 1.7 million Latinas are not working due to child and elder care responsibilities. Further, more than half of Latino families live in areas with low licensed child care capacity.48 Those Latino families with access to child care often cannot afford the cost, especially low-income and working-class Latinas.49 Early childhood spending and child care subsidies can help reduce the costs while promoting greater gender equity and higher workforce participation among women.50

To promote an equitable recovery and reentrance into the workforce, Congress should improve access to child care through subsidies and increased child care quality and availability. Renewing federal subsidy programs such as the American Rescue Plan’s Child Tax Credit (CTC)51 would improve child care affordability; one in four families with young children used their CTC monthly payments to cover child care costs.52 Passing the Build Back Better Act would also minimize child care costs by capping them at 7% of a household’s income.53 A third option, The Murray-Kaine proposal, would provide families with child care subsidies through the Community Development Block Grant program.54 All three efforts provide funding to increase child care supply and worker wages55 and reduce child care costs for low- and middle-income families.56

Direct and continuous federal child care funding would allow states to develop child care programs. As part of the American Rescue Plan, states received $39 billion in dedicated child care relief funding. New Mexico, the state with the highest child poverty rate and the largest Latino share of residents,57 used federal funding to improve its early childhood system. As of 2022, the state is providing one year of free child care to residents earning up to 400% of the federal poverty line.58States should also implement high-quality universal preschool programs and adopt their own child care tax credits. As of 2020, 44 states and DC offered preschool programs, yet only five states59 had invested enough to provide high-quality, full-day preschool for all their 3- to 4-year-old children. State-level Earned Income and Child Tax Credits can backstop federal support for child care.60 - Permanently expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Latina labor force participation remains the farthest from pre-pandemic levels. The jobs available to many Latinas—especially immigrants or those with less formal education—do not provide enough money to make entering the workforce worthwhile. For nearly half of Latinas earning less than $15 an hour,61 tax credits can provide an additional incentive and the funding to make work feasible.

For instance, the EITC is a fully refundable tax credit for low- and moderate-income working families with children. Recipients must have wages from a job to qualify. As their earnings rise, the credit amount grows until reaching the maximum limit, incentivizing recipients to join the workforce and increase their hours.62 The EITC was the most important factor in boosting employment for women heads of households in the 1990s.63

However, from 2013 to 2015, only 46% of eligible Latino families filed and received an EITC credit, compared to 55% of white families.64 Current rules also exclude workers without children, workers ages 19-24 and over 65, and workers without Social Security numbers.65 The American Rescue Plan temporarily changed some of these requirements and increased the maximum credit value and qualifying income limits, 66 extending assistance to an additional 3.6 million Latino workers.67 Congress should make these changes permanent and expand access to workers with individual taxpayer identification numbers (ITINs) to facilitate re-entry into the workforce.68 Congress should pair expansions with funding for Spanish-language outreach efforts69 and free tax preparation services70 to ensure qualifying immigrant Latinas can access much-needed relief. - Strengthen education and training programs to up-skill Latinas. As LPPI research has previously found, Latinas lack access to high-quality, stable employment that would provide them with the resources to adequately care for their families. Access to high-quality jobs begins with education and training. While higher levels of education generally lead to better wages and benefits, few Latinas have completed college.71

Federal and state governments should fund programs to improve educational attainment among Latinas and other students of color, especially financial assistance and K-12 pipeline programs to recruit underrepresented students.72 Latino students were also more likely to delay or extend plans for higher education because of financial constraints exacerbated by the pandemic.73 To tackle these barriers, Congress should reintroduce legislation to offer tuition-free community college to students across the country—as initially proposed in the Biden administration’s Build Back Better Plan.74

Additionally, universities and colleges should establish transfer pathways from community colleges to four-year universities, support returning students through access to financial aid and priority registration, and help student-parents through targeted advising and free or subsidized child care. More tailored workforce development initiatives and apprenticeships can also provide Latinas with employable and transferable skills through vocational training, education, and access to quality career-ladder jobs.75

- Provide child care subsidies and improve child care quality, affordability, and availability. The Household Pulse Survey data show that 1.7 million Latinas are not working due to child and elder care responsibilities. Further, more than half of Latino families live in areas with low licensed child care capacity.48 Those Latino families with access to child care often cannot afford the cost, especially low-income and working-class Latinas.49 Early childhood spending and child care subsidies can help reduce the costs while promoting greater gender equity and higher workforce participation among women.50

- Provide support and flexibility for Latinas and their families when caretaking needs arise.

- Establish federal and state paid family and medical leave programs. In moments of crisis or unforeseen change, paid family and medical leave benefits allow workers to take time off while maintaining their incomes and jobs. This benefit is particularly important in helping women with less education keep their jobs76 and assisting new mothers to return to work.77 However, Latinas were the least likely group to take paid leave throughout the pandemic. Few Latinas had access to employer-provided paid leave benefits,78 and while 42.7% of Latino parents have access to unpaid leave, only 26% can afford to take unpaid leave.79 Further, no federal paid leave program exists, making the United States an outlier among advanced countries.80

As the Build Back Better Act proposed, Congress should create a federal program to provide paid family and medical leave for workers. Under the Act, all workers would receive four weeks of paid family leave to care for severe health needs, care for loved ones, or bond with new children.81 While a federal leave program would ideally provide six months of paid leave,82 the introduction of a paid family leave program of any length would support Latina families and strengthen the U.S. social infrastructure system.

In the absence of federal action, state legislatures should also consider creating their own paid family leave programs. California’s Paid Family Leave law, for instance, provides eight weeks of paid leave to bond with a new child or care for a seriously ill child, partner, or parent. The program is funded through payroll taxes and pays employees 55% of their weekly wages.83 While California’s paid leave policy does not include a job guarantee, it has resulted in more parents taking leave and spending more quality time with their children.84 - Compensate family caregivers and reform unemployment insurance to include part-time workers providing care. Latinas who choose or need to remain at home to care for their families should receive some form of compensation for their household work. Canada85 and several European countries provide cash assistance called universal child benefits—regardless of employment status—to families with children.86 Countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany also offer pension credits to parents who leave the workforce to care for young children or aging parents.87 One recent U.S. proposal, the Rise Credit, would replace the EITC and provide caregivers of young children with a maximum annual tax credit ($4,000 for single parents and $8,000 for married couples).88

Other possibilities include extending the EITC to unpaid family caregivers,89 creating Social Security credits for people who leave the workforce to care for family,90 and reforming state-level eligibility for unemployment insurance (UI).91 Existing UI eligibility criteria in many states disqualify workers forced to leave their jobs or shift to part-time work due to caregiving responsibilities. Loosening these restrictions would expand eligibility to women of color across the country who are overrepresented in part-time work92 and were more likely to lose or leave a job during the COVID-19 pandemic.93 Regardless of the specific form financial assistance takes, unpaid caregivers—especially Latinas—need it to ensure their long-term economic stability.

- Establish federal and state paid family and medical leave programs. In moments of crisis or unforeseen change, paid family and medical leave benefits allow workers to take time off while maintaining their incomes and jobs. This benefit is particularly important in helping women with less education keep their jobs76 and assisting new mothers to return to work.77 However, Latinas were the least likely group to take paid leave throughout the pandemic. Few Latinas had access to employer-provided paid leave benefits,78 and while 42.7% of Latino parents have access to unpaid leave, only 26% can afford to take unpaid leave.79 Further, no federal paid leave program exists, making the United States an outlier among advanced countries.80

Conclusion

Latinas are the backbones of their families and supported their households during a grueling season unlike any other. In 2021, they spent the least time working for pay or profit of any group, and the most time caring for their homes and household members. As a result of their caregiving and household responsibilities, many Latinas could not work for compensation, and more Latinas did not work relative to other women. While 2021 marked a return to many pre-pandemic trends, Latinas continued to work in their households at a higher rate than in 2019.

Latinas balance a multitude of roles: they are moms, parental caretakers, household managers, and employees. They and all other caregivers should be able to support their families without risking their careers or financial stability. To achieve an equitable economic recovery, we must build social infrastructure that prevents workers from having to choose between their work and their family, create high-quality and flexible jobs, and compensate unpaid caregivers for the value their familial and household labors generate. Together, these policies would give Latinas and other workers genuine opportunity and autonomy over their career and family decisions.

Endnotes

1 Sol Espinoza, “Closing the Latina Wealth Gap: Building an Inclusive Economic Recovery After COVID” (Washington, DC: UnidosUS, April 19, 2021), available online.

2 Jeff Hayes, Cynthia Hess, and Tanima Ahmed, “Providing Unpaid Household and Care Work in the United States: Uncovering Inequality,” Briefing Paper (Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research, January 20, 2020), available online.

3 Kassandra Hernández, Diana Garcia, Paula Nazario, Michael Rios, and Rodrigo Dominguez-Villegas, “Latinas Exiting the Workforce: How the Pandemic Revealed Historic Disadvantages and Heightened Economic Hardship” (Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute, June 2021), available online.

4 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Situation News Release: May 2020,” with monthly archives available online.

5 Hernández et al., “Latinas Exiting the Workforce.”

6 Gus Wezerek and Kristen R. Ghodsee, “Women’s Unpaid Labor Is Worth $10,900,000,000,000,” The New York Times, March 5, 2020 available online.

7 Alexandra Finley, “Women’s Household Labor Is Essential. Why Isn’t It Valued?,” Washington Post, May 29, 2020, available online.

8 Ibid.

9 This report includes all Latinas included in the American Time Use Survey—civilian, noninstitutionalized residents ages 15 and older.

10 Caring for household members or family refers to time individuals spend on activities to care for any adult or child in their household—for example, providing physical, medical, or personal care. Household maintenance refers to the time individuals spend maintaining their households, including (but not limited to) housework, cooking, yard and pet care, vehicle maintenance, and repair and home maintenance.

11 Because the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey only asks whether a person has worked in the last seven days, we cannot formally determine whether someone has temporarily stopped working, become unemployed, or left the workforce entirely.

12 Gretchen Livingston, “Among Hispanics, Immigrants More Likely to Be Stay-at-Home Moms and to Believe That’s Best for Kids” (Washington, DC: Pew Research, April 2014), available online.

13 Hayes et al., “Providing Unpaid Household and Care Work in the United States: Uncovering Inequality.”

14 Hernández et al., “Latinas Exiting the Workforce.”

15 “Caregiver Profile: The Hispanic/Latino Caregiver” (Washington, DC: National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP Public Policy Institute, August 2015), available online.

16 “Fact Sheet: The ‘Typical’ Hispanic Caregiver” (Washington, DC: National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP Public Policy Institute, May 2020), available online.

17 Luisa Blanco, Vanessa Cruz, Deja Frederick, and Susie Herrera, “Financial Stress Among Latino Adults in California During COVID-19,” Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy 5 (August 2, 2022): 134–48 (2022).

18 Elise Gould and Melat Kassa, “Low-Wage, Low-Hours Workers Were Hit Hardest in the COVID-19 Recession: The State of Working America 2020 Employment Report” (Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, May 20, 2021), available online.

19 Emma K. Lee, Kevin Ferreira van Leer, Zach Parolin, and Danielle Crosby, “Hispanic Families’ Experiences of Child Care Closures During COVID-19” (National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, October 15, 2021), available online.

20 Livingston, “Among Hispanics, Immigrants More Likely to Be Stay-at-Home Moms and to Believe That’s Best for Kids.”

21 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Situation News Release,” with monthly archives available online.

22 Emma K. Lee, Kevin Ferreira van Leer, Zach Parolin, and Danielle Crosby, “Hispanic Families’ Experiences of Child Care Closures During COVID-19” (National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, October 15, 2021), available online.

23 Yiyu Chen, Kevin Ferreira van Leer, and Lila Guzman, “Many Latino and Black Households Made Costly Work Adjustments in Spring 2021 to Accommodate COVID-Related Child Care Disruptions” (National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families, October 12, 2021), available online.

24 Benjamin Hansen, Joseph J. Sabia, and Jessamyn Schaller, “Schools, Job Flexibility, and Married Women’s Labor Supply: Evidence From the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Working Paper (National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2022), available online.

25 Liana Christin Landivar, Leah Ruppanner, Lloyd Rouse, William J. Scarborough, and Caitlyn Collins, “School Reopenings During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Implications for Gender and Racial Equity,” Demography 59, no. 1 (February 1, 2022): 1–12.

26 Ibid.

27 Darriya Starr, Niu Gao, and Caroline Danielson, “Pandemic-Strained Parents Sacrifice Work to Care for Their Children” (San Francisco, CA: Public Policy Institute of California, February 2022), available online.

28 Wezerek and Ghodsee, “Women’s Unpaid Labor Is Worth $10,900,000,000,000.”

29 Finley, “Women’s Household Labor Is Essential. Why Isn’t It Valued?”

30 Luis Noe-Bustamante, Jens Manuel Krogstad, and Mark Hugo Lopez, “For U.S. Latinos, COVID-19 Has Taken a Personal and Financial Toll” (Washington, DC: Pew Research, July 2021), available online.

31 Tests of statistical significance for these comparisons are presented in Appendix Tables 1 and 2.

32 Sandra L. Hofferth, Sarah M. Flood, Matthew Sobek, and Daniel Backman, “American Time Use Survey Data Extract Builder: Version 2.8 [Dataset]” (College Park, MD: University of Maryland and Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2020), available online.

33 These categories reflect the time use tables published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, not those coded by IPUMS. These variables include BLS_HHACT (household activities), BLS_WORK (Work-related activities), and BLS_CAREHH (caring for household members).

34 For 2020, we used the COVID-appropriate person weights provided by IPUMS to account for the partial-year data collection in 2020 (variable WT20). Additionally, as noted, we filter out any observations in 2020 for which the month of interview is less than 5. See Flood et. al (March 2022) and the IPUMS documentation on the Month variable for more information. For all other years, we use the full calendar year data and person weights based on the 2006 methodology (WT06). Jeff Hayes, Cynthia Hess, and Tanima Ahmed also use the American Time Use survey microdata to uncover inequalities in unpaid household and care work. For more detail, see “Providing Unpaid Household and Care Work in the United States: Uncovering Inequality,” available online.

35 Sarah M. Flood, Katie R. Genadek, Kelsey J. Drotning, and Liana C. Sayer, “Navigating COVID-19 Disruptions in U.S. Time Diary Data,” Working Paper (Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota, March 2022), available online.

36 U.S. Census Bureau, “Measuring Household Experiences during the Coronavirus Pandemic,” accessed June 1, 2022, available online.

37 “Census Pulse Public Use Files: Questionnaire Two,” Urban Institute Data Catalog, last updated July 26, 2022, available online.

38 Despite going from a one- to a two-week collection period, the Household Pulse Survey calls collection periods “weeks” to maintain continuity with Phase 1.

39 This report analyzes all phases of the Household Pulse Survey from Phase 2 onward, including Phases 3, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5. From Phase 2 onward, the possible responses for why a person has not worked in the last seven days have remained the same, allowing for consistent comparisons. Beginning with Phase 3.1 (April 14, 2021), the Census Pulse also began to ask about child care disruptions. Additionally, the timing and frequency of the Census Pulse Survey has changed as the survey has gone on. During Phase 1 of the survey (April 23, 2020 to July 21, 2020), the data were collected and disseminated on a weekly basis. However, all later phases of the survey have used two-week collection and dissemination periods. Phase 3.3 also shifted to a two-weeks-on, two-weeks-off collection approach.

40 See also Hernández et al., “Latinas Exiting the Workforce: How the Pandemic Revealed Historic Disadvantages and Heightened Economic Hardship.”

41 Alyssa Fowers, “The Economy Is Getting Even Worse for Americans with a High School Diploma or Less Education,” Washington Post, January 27, 2021, available online.

42 Randy Capps, Jeanne Batalova, and Julia Gelatt, “Immigrants’ U.S. Labor Market Disadvantage in the COVID-19 Economy: The Role of Geography and Industries of Employment” (Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, September 28, 2021), available online.

43 Gould and Kassa, “Low-Wage, Low-Hours Workers Were Hit Hardest in the COVID-19 Recession”; Capps et al., “Immigrants’ U.S. Labor Market Disadvantage in the COVID-19 Economy.”

44 LPPI analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, weeks 28-48.

45 Hernández et al., “Latinas Exiting the Workforce.”

46 Shengwei Sun, “Part-Time Working Caregivers Need Unemployment Insurance Reform” (Washington, DC: National Women’s Law Center, June 2022), available online.

47 Claudia Olivetti and Barbara Petrongolo, “The Economic Consequences of Family Policies: Lessons from a Century of Legislation in High-Income Countries,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31, no. 1 (February 2017): 205–30.

48 Rasheed Malik, Katie Hamm, Leila Schochet, Cristina Novoa, Simon Workman, and Steven Jessen-Howard, “America’s Child Care Deserts in 2018” (Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, December 2018), available online.

49 Maura Baldiga, Pamela Joshi, Erin Hardy, and Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, “Child Care Affordability for Working Parents” (Waltham, MA: Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy, Brandeis University, November 2018), available online.

50 Olivetti and Petrongolo, “The Economic Consequences of Family Policies.”

51 White House, “The Child Tax Credit,” (Washington DC: The White House), accessed on August 19, 2022, available online.

52 Daniel J. Perez-Lopez and Yeris Mayol-Garcia, “Parents with Young Children Used Child Tax Credit Payments for Child Care” (Washington D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, April 13, 2022), available online.

53 Rasheed Mailk, “The Build Back Better Act Substantially Expands Child Care Assistance” (Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, December 2021), available online.

54 Sharon Parrott, “Murray-Kaine Proposal to Expand, Improve Child Care Would Benefit Families and the Economy” (Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 18, 2022), available online.

55 Ibid; Amanda Guarino, “FAQ on the Child Care and Preschool Provisions in the Build Back Better Act” (Washington, DC: First Five Years Fund, December 2021), available online.

56 Ibid; Jonathan Borowsky, Jessica H. Brown, Elizabeth E. Davis, Chloe Gibbs, Chris M. Herbst, Aaron Sojourner, Erdal Tekin, and Matthew J. Wiswall, “An Equilibrium Model of the Impact of Increased Public Investment in Early Childhood Education,” NBER Working Paper 30140 (National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2022), available online.

57 Alieza Durana, “Case Study: Care in New Mexico” (Washington, DC: New America, September 2016), available online.

58 Casey Parks, “New Mexico to Offer a Year of Free Child Care to Most Residents,” Washington Post, April 28, 2022, available online.

59 Allison H. Friedman-Krauss, W. Steven Barnett, Karin A. Garver, Katherine S. Hodges, G.G. Weisenfeld, and Beth Ann Gardiner, “The State of Preschool 2020” (New Brunswick, NJ: The National Institute for Early Education Research, 2021), available online.

60 Tax Credits for Workers and Families, “State Tax Credit,” (2022), accessed on July 20, 2022, available online.

61 Andrew Van Dam, “Fewer Americans Are Earning Less than $15 an Hour, but Black and Hispanic Women Make up a Bigger Share of Them,” Washington Post, March 3, 2021, available online.

62 Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, Arloc Sherman, and Brandon DeBot, “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds” (Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 2015), available online.

63 Austin Nichols and Jesse Rothstein, “The Earned Income Tax Credit,” in Economics of Means-Tested Transfer Programs in the United States, Volume 1 (University of Chicago Press, 2015), 137–218.

64 Dana Thomson, Lisa A. Gennetian, Yiyu Chen, Hannah Barnett, Madeline Carter, and Santiago Deambrosi, “State Policy and Practice Related to Earned Income Tax Credits May Affect Receipt among Hispanic Families with Children” (Bethesda, MD: Child Trends, November 2020), available online.

65 Internal Revenue Service, “Publication 596, Earned Income Credit (EIC),” accessed June 9, 2022, available online.

66 Areeba Haider and Galen Hendricks, “Now Is the Time To Permanently Expand the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit” (Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, May 2021), available online.

67 Chuck Marr, Kris Cox, Stephanie Hingtgen, and Katie Windham, “Congress Should Adopt American Families Plan’s Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions Permanent” (Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 2021), available online.

68 Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, Abigail N. Walters, Leah Shafer, Elizabeth Wong, and Pamela Joshi, “A Policy Equity Analysis of the EITC: Fully Including Children in Immigrant Families and Hispanic Children in This Key Anti-Poverty Program” (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, April 2022), available online.

69 Thomson et al., “State Policy and Practice Related to Earned Income Tax Credits May Affect Receipt among Hispanic Families with Children.”

70 Xiaohan Zhang and Jason Saving, “Greater Hispanic Outreach Can Improve Take-Up of Earned Income Tax Credit” (Dallas, TX: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, March 2022), available online.

71 Hernández et al., “Latinas Exiting the Workforce.”

72 Ibid.

73 Taemin Anh and Rodrigo Dominguez-Villegas, “A Change of Plans: How the Pandemic Affected Students of Color and Their Plans for Higher Education” (Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute, March 15, 2022), available online.

74 White House, “Fact Sheet: How the Build Back Better Plan Will Create a Better Future for Young Americans” (Washington, DC: White House, July 22, 2021), available online.

75 Misael Galdámez and Nick González, “More than Solidarity: How Labor Unions Preserved Latino Jobs” (Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute, September 6, 2021), available online.

76 Olivetti and Petrongolo, “The Economic Consequences of Family Policies.”

77 Charles L. Baum II and Christopher J. Ruhm, “The Effects of Paid Family Leave in California on Labor Market Outcomes,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 35, no. 2 (2016): 333–56.

78 Ann P. Bartel, Soohyun Kim, Jaehyun Nam, Maya Rossin-Slater, Christopher Ruhm, and Jane Waldfogel, “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to and Use of Paid Family and Medical Leave: Evidence from Four Nationally Representative Datasets,” Monthly Labor Review (Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 2019), available online.

79 Pamela Joshi, Maura Baldiga, and Rebecca Huber, “Unequal Access to FMLA Leave Persists” (Waltham, MA: Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy, Brandeis University, January 2020), available online.

80 Alexis Gould-Worth, “Paid Sick Time and Paid Family and Medical Leave Support Workers in Different Ways and Are Both Good for the Broader U.S. Economy” (Washington, DC: Center for Equitable Growth, January 2022), available online.

81 Claire Cain Miller, “The World ‘Has Found a Way to Do This’: The U.S. Lags on Paid Leave,” The New York Times, October 25, 2021, available online.

82 Research has shown that leave policies longer than a year can negatively affect women’s labor force outcomes. For more details, see Maya Rossin-Slater and Jenna Stearns, “The Economic Imperative of Enacting Paid Family Leave Across the United States” (Washington, DC: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, February 18, 2020), available online.

83 “State Family and Medical Leave Laws,” National Conference of State Legislatures, July 13, 2022, available online.

84 Recent research has been mixed on the effect of California’s paid family leave law on women’s labor outcomes. In contrast to earlier research, Bailey, Byker, Patel, and Ramnath found little evidence that paid family leave increased women’s employment, wage earnings, or attachment to employers. For more details, see: Martha J. Bailey, Tanya S. Byker, Elena Patel, and Shanthi Ramnath, “The Long-Term Effects of California’s 2004 Paid Family Leave Act on Women’s Careers: Evidence from U.S. Tax Data,” NBER Working Paper No. 26416 (National Bureau of Economic Research, October 2019), available online.

85 Arloc Sherman, “Canadian-Style Child Benefit Would Cut U.S. Child Poverty by More Than Half,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 24, 2018, available online.

86 Dylan Matthews, “Sweden Pays Parents for Having Kids—and It Reaps Huge Benefits. Why Doesn’t the U.S.?,” Vox, May 23, 2016, available online.

87 Alicia H. Munnell and Andrew D. Eschtruth, “Modernizing Social Security: Caregiver Credits,” Brief, Number 18-15 (Boston, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, August 2018), available online.

88 “Rise Credit” (Washington, DC: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, May 22, 2019), available online.

89 Gene Sperling, “Chapter Nine: Work and Economic Dignity” in Economic Dignity (New York City, NY: Penguin Random House, 2020), p. 161.

90 Claire Cain Miller, “Stay-at-Home Parents Work Hard. Should They Be Paid?,” The New York Times, October 3, 2019, available online.

91 Sun, “Part-time Working Caregivers Need Unemployment Insurance Reform.”

92 Ibid.

93 Hernández et al., “Latinas Exiting the Workforce.”