Latino is Not a Race: Understanding Lived Experiences Through Street Race

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rosario Isabel Majano, MS, and Dr. Rodrigo Dominguez Villegas for their insightful reviews of this report. Additionally, with the title of this report, we would like to thank and acknowledge the “Latino is Not a Race” campaign. This campaign, launched in February 2023, was a collective effort led by the afrolatin@ forum and supported by over 35 AfroLatine organizations and individuals. Together with more than 100 scholars, the campaign worked to highlight the fact that ‘Latino’ is an ethnicity, not a race, and to elevate AfroLatine representation.

Executive Summary

Since its origin, the United States (U.S.) Census has captured data on the race of people living within its borders, at first as a tool to uphold the enslavement and segregation of Black people.1 Today’s Census questions on racial and ethnic identification reflect shifts in societal understandings of race, negotiations between interest groups, and governmental priorities regarding civil rights.2 For example, the Census Bureau added a separate question on Hispanic ethnicity to the 1980 Census only after the passage of key civil rights legislation and sustained pressure from Hispanic advocacy groups, like the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund (MALDEF) and Aspira.3

Census demographic data is vital in distributing federal and state resources, making it essential to have accurate population counts of marginalized communities.4 And yet the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which creates guidelines for federal data collection on race and ethnicity, has not defined race (a social status based on the social meanings associated with one’s physical/visual characteristics) or ethnicity (origins, cultural background, nationality, or ancestry) in data collection instruments asking about the two.5 The lack of conceptual clarity has been especially detrimental to Black Latino communities who have suffered from undercounts as a result.6

On March 28, 2024, the OMB announced several critical changes to federal surveys that inquire about demographic characteristics, including the adoption of a single-question format to ask about race and ethnicity. In this format, all federal agencies will adopt “Latino/Hispanic” as a co-equal racial category instead of recording it as a separate ethnic origin, as it has been since 1977.7 Though some Latino advocacy groups recommended this decision, others—particularly those representing Afro-Latinxs—have continually opposed the proposal.8,9 They argue that Latino10 communities in particular are at risk of being misrepresented in data due to this new question format and how data are analyzed by the Census Bureau.11,12 For example, those who designate a Latino ethnicity alongside a racial identification (e.g., white or Black) risk being designated by the Census Bureau as “multiracial” rather than a person of Latino ethnicity who is a certain race.13 Additionally, the Census has historically prioritized its own idea of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity as descending from a Spanish-speaking heritage, and therefore excludes groups like Brazilians. These issues call into question the principle of self-identification and could also render Afro-Latinxs and other groups more invisible.14

While the OMB has solidified its decision about the single-question format for at least the 2030 Census, the public can still advocate for new questions to be added to future decennial Censuses and other federal surveys, such as the American Community Survey (ACS). Some scholars have advocated for including a question about “street race,” or the perceived race that a stranger would assume you to be based on physical appearance.15 This question could allow people to continue to designate their self-identified racial identity in the new single-format race question where they can mark one or more options, while also denoting their street race where they mark only one category—recognizing that experiences of racism and discrimination are closely related to one’s visible racial status.16 Recent research has illuminated that asking about street race can generate a more nuanced understanding of Latinos and how they are racialized in public health and civil rights research.17 The further inclusion of a street race question in federal data collection instruments is vital to ensuring intersectional policy interventions in the future.

We offer the following policy recommendations with the goal of bettering outcomes for Latinos in the U.S.:

- The current OMB guidelines do not prohibit adding additional questions on race and ethnicity. The U.S. Census and other demographic data instruments should include a question about street race.

- The OMB and the Census Bureau should clarify that race, ethnicity, and nationality are analytically distinct and define these terms for all federal data collection instruments.

- The OMB should ensure Census coding procedures accurately reflect the racial and ethnic self-identification of respondents.

- The federal government should allocate additional funding to advance research on best practices for collecting and analyzing race and ethnicity data.

Though the “Latino” identity remains essential to our shared political mobilization, we must continue to recognize the ways our differences have also created disparities within our community.18 An essential first step in fighting inequities and creating space for the needs of the Afro-Latinx population is to improve current federal estimates of how many Latinos are racialized as Black and subjected to anti-Blackness.19 The inclusion of street race does not do away with racial self-identification, but rather acknowledges the continued oppression of visible minorities. By asking about ethnic origin, racial identity, and street race, we can capture data on how race is encountered and experienced in the daily lives of the U.S. population and fight against institutional racism and anti-Black discrimination.

Introduction: A Brief History of the Census and the “Race” Question

As mandated by the U.S. Constitution, Article I, Sections 2 and 9, the U.S. is to conduct a Census, or a complete count of all the people living in the U.S. or U.S. territories, regardless of citizenship or immigration status, every decade.20 The U.S. conducted its first Census in 1790, and the results were used to allot state Congressional seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. This early version had six questions, including one on race that grouped people into three categories: “free white people,” “all other free persons,” and “slaves.”

As the Census Bureau website notes, the race and ethnicity categories presented on the Census reflect “a social definition of race recognized in this country.”21 As such, Census racial categories have frequently evolved in response to the shifting cultural and social environment of the times. Until the first mail-out Census in 1960, in-person Census-takers would assign race based on their observations of an individual’s characteristics,22 unlike the racial and ethnic self-identification that occurs today. The passage of key civil rights legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, required collecting improved demographic data to enforce these laws effectively, leading to further adaptations.23 Until 2000, individuals were limited to one racial identification, while respondents today can select multiple options.

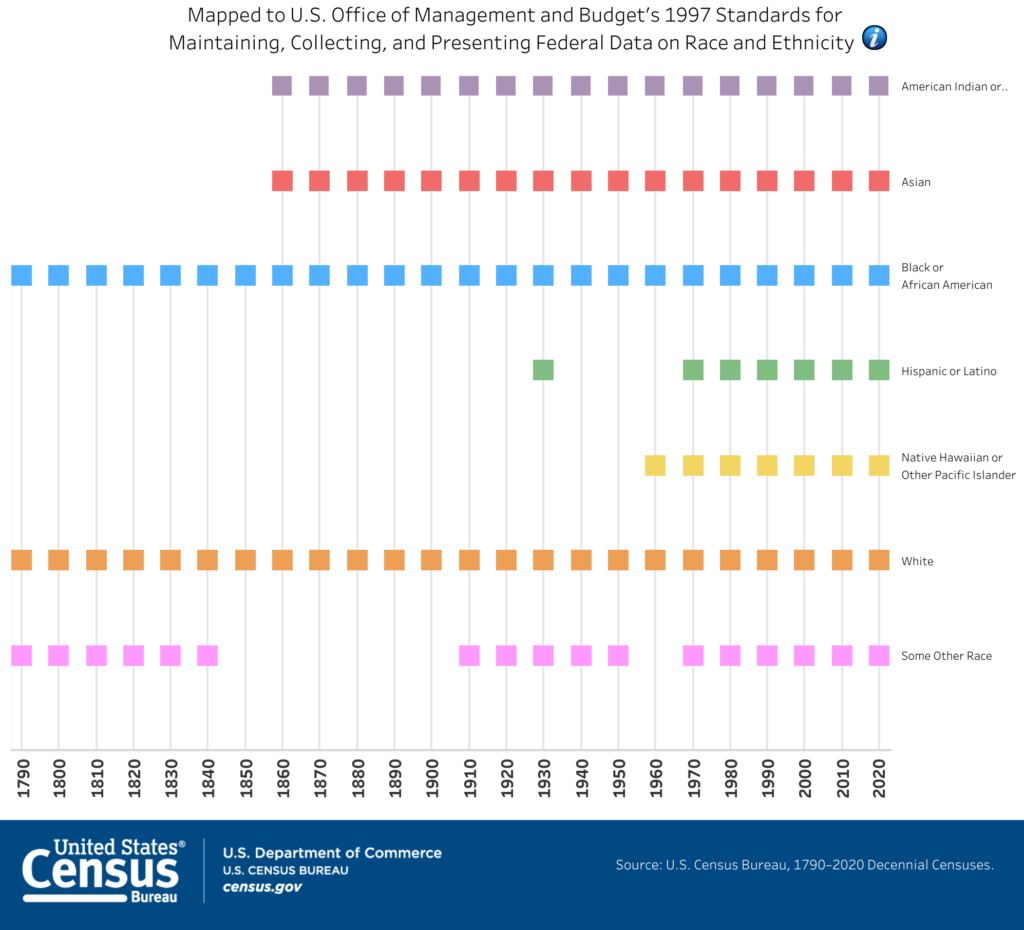

The below figure by the Census Bureau illuminates how the measurement of race and ethnicity has developed over the decades.24

U.S. Decennial Census Measurement of Race and Ethnicity Across the Decades, 1790-2020

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, available online.

To harmonize data collection across various federal agencies, the OMB developed Statistical Policy Directive No. 15 (SPD 15) in 1977, which provided the minimum data standards for use across the federal government. The race categories included the options “American Indian or Alaskan Native,” “Asian or Pacific Islander,” “Black,” and “White.” The directive also noted that “it is preferable to collect data on race and ethnicity separately” with two options for ethnicity – “Hispanic origin” or “Not of Hispanic Origin.”25

The inclusion of Hispanic and Latino populations in Census counts has remained a challenge for the OMB. The Census first began collecting separate data on “Mexicans” as a racial category in 1930, but dropped the category in the 1940 Census, noting that “Mexicans are to be regarded as White unless definitely of Indian or other nonwhite race.”26 In part, this decision to categorize Mexicans broadly as white was due to the advocacy of the League of the United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), who argued that Mexicans were a white race.27 While the Census would not again collect data on Latinos as a separate “origin” category until the 1970 Census, it did collect data on Spanish surnames, language spoken at home, and the respondent’s place of birth or parent’s place of birth in a Spanish-speaking country.28

In 1970, the Census Bureau added a question on Hispanic origin to the Census as a separate question of ethnicity late in the planning process. Therefore, this Census only included the Hispanic origin question in the long-form version of the questionnaire sent to just five percent of U.S. households, resulting in a significant undercount of the Hispanic/Latino population.29 In response, Hispanic advocacy groups, like the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund (MALDEF) and ASPIRA, placed pressure on the federal government to accurately count the Latino population in the next Census.30

In 1976, Congress passed Public Law 94–31, requiring federal agencies to collect, analyze, and publish statistics on persons of Spanish origin or descent.31 The Census Bureau also formed a Spanish-origin advisory committee composed mainly of Mexican-American, Puerto Rican, and Cuban civil rights leaders to explore adding a Spanish-origin category to the Census.32 Finally, the Census Bureau added a separate question on Hispanic ethnic origin for the 1980 Census. The question first appeared after the race question and asked, “Is this person of Spanish/Hispanic origin or descent?” with possible responses including: “No (not Spanish/Hispanic); Yes, Mexican, Mexican-Amer., Chicano; Yes, Puerto Rican; Yes, Cuban; Yes, other Spanish/Hispanic.”33

Census identification markers assume that those who are Hispanic/Latino are of Spanish-speaking heritage(s). For example, the Census’ Hispanic/Latino identification allows for the inclusion of European Spaniards as members of the Hispanic or Latino ethnic group, but excludes other groups like Brazilians because they do not come from a Spanish-speaking country or have Spanish or Spanish-speaking heritage.34 Additionally, these identification markers call into question the principle of racial and ethnic self-identification put forward by the Census Bureau, as there is an established logic as to whom the Census Bureau considers Hispanic or Latino that seems to run contrary to Latinos’ own views of themselves.

Latino is Not a Race

Despite the Census’ narrow understanding of the markers of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, there has never been one way that Latinos have looked or self-identified in the U.S., either socially or in governmental documents.35 As people from Latin America immigrate to the U.S., they bring with them a complicated history and understandings of themselves defined by skin color, race, class, ethnic origin, etc.36 Historically, racial self-identification for Latinos is informed by their local, ethnic, and racial context.37 Part of the work of applying intersectionality—defined by scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw as “a metaphor for understanding the ways that multiple forms of inequality or disadvantage sometimes compound themselves and create obstacles that often are not understood”38—is ensuring that differences in how Latinos self-identify and experience race is understood and analyzed in demographic data.

Many Latinos continue to struggle to identify with any of the OMB racial categories presented in government surveys and instead adopt Latinidad as their dominant identity.39 Some may choose to specify no race, one or more races, all provided races, or “some other race” if no “Brown” category is provided.40

Thus, essential to creating accurate counts of Latino populations is considering the perspective of Latinos who identify as “Brown.” Although the Brown identity has roots in Latin American campaigns of mestizaje and the adoption of moreno as a classification, it has continued to be an essential part of the U.S. Latino political discourse, especially amongst Mexican-American communities in the Southwest.41 Today, the Brown identity continues to be relevant in conversations around criminal justice, immigration detention, and voting rights.42 Brownness is an essential part of understanding how race-based discrimination functions in the Latino community.43

Coding Concerns in OMB Analysis of Census Race and Ethnicity Data

The 2020 Census asked respondents about their race and ethnicity as follows:44

While these example prompts are meant to be guides to help respondents fill out the Census, they demonstrate flaws in the understanding of race and ethnicity that are analytically problematic for a person who enters an origin not concordant with the OMB’s defined race groups.45 Except for “American Indian,” no other race box lists a Latino or Hispanic origin, allowing for confusion in interpretation. Many of the example prompts listed under race groups, such as German or Jamaican, are actually national origins. Listing them under race categories creates confusion for racial minorities from these countries and contributes to the falsehood that national origins are linked to race.46 For this reason, some scholars have advocated for eliminating these national origin example prompts, simply allowing individuals to interpret the listed races for themselves.47

Additionally, flaws in Census data collection, analysis, and reporting can lead to the misclassification of Latinos as “two or more races,” coding them as multiracial, when that was likely not the intention of the respondent.48 According to former Census Bureau Statistician Dr. Ricardo Henrique Lowe, Jr., the current coding logic behind the Census reassigns responses at times involuntarily through a process called back coding or residual coding. He writes, “If a person of Hispanic or Latino origin such as myself writes Panamanian under the Black category, the Bureau would automatically code that response as Black and Some Other Race,”49 resulting in an observation of a multiracial Latino, rather than a Black-alone Latino. Similarly, if an individual from a non-Spanish-speaking Caribbean country, such as Haiti, identifies themselves as Hispanic/Latino on the Census and writes “Haitian” as their specific ethnic origin,50 they may be coded as Black alone and removed from the Hispanic/Latino count.51 These Census Bureau coding decisions contribute to the undercount of Afro-Latinxs. These choices are concerning given that the OMB itself publicly acknowledges that Latinos “may be of any race.”52

Back coding self-identification responses is also a challenge for Brazilian respondents—a group that largely identifies as Latino and has a substantial Black population—who the Census Bureau does not recognize as Latino and therefore automatically assigns to “some other race.”53 These coding issues may worsen under the newly adopted combined question race/ethnicity format, as origin, ethnicity, and race are further conflated.

2024 OMB Revisions to Statistical Policy Directive No. 15

The March 2024 revisions to SPD 15 represent the first set of changes made to the policy since 1997 and perhaps one of the most significant shifts from the original language and goals of the 1977 directive.54 Leading up to the decision, the OMB began a working group in 2022 of federal staff with data collection and analysis experience. They heard over 20,000 public comments, held 94 public listening sessions, and conducted three public town halls to receive feedback. Ultimately, the OMB decided to move forward with a redesign of certain elements of the Census demographics section. One significant change is that Hispanic/Latino ethnicity will now be adopted as co-equal with race categories (such as white, Black, etc.) and no longer be asked as a separate ethnicity question.55 Respondents will still be allowed to mark as many categories as applies to them.

Below is an example from the OMB of how the race and ethnicity question may be formatted in the 2030 Census:56

During the public comments period before the official decision was made, responses from Latino advocacy groups varied in their support or opposition to the single-question format. Some argued that this change would lead to better-quality data,57 as it more closely reflected how many Latinos self-identify and could solve the issue of Latinos overwhelmingly using the “some other race” category. In the 2020 Census, 90.8% of “some other race” respondents were of Hispanic or Latino origin.58 While this category allows individuals to express that they do not feel captured by the predetermined race categories, it obscures the fact that racial identity affects how people experience society, positively or negatively. It also has material consequences on the allocation of federal and state funding to marginalized communities. A catch-all “some other race” category is not helpful analytically for understanding the racial status and accompanying lived experiences and social inequities of the millions of people who identify this way.

However, other Latino advocacy groups, especially those groups representing the Afro-Latinx community, voiced concerns that the SPD 15 change will be to the detriment of Black Latinos and other Latinos who prefer to designate their race and Latino ethnicity rather than Latino ethnicity alone. They point to evidence that in a single-question format, Afro-Latinxs are less likely to designate themselves as both Black and Latino and are more likely to simply choose one category,59 possibly leading to future undercounts of Afro-Latinx individuals, as well as harm to the broader Black and Latino counts.60 They expressed concern about further coding issues like the ones mentioned above. Advocacy organizations also argue that a single-question format conflates our understanding of race and ethnicity in ways that harm both self-identification and our understanding of discrimination. For these reasons, over 100 scholars and advocates signed onto the Afro-Latino Coalition’s “Latino is not a Race” Campaign, expressing these concerns to the OMB.61

Implications of Data Collection on Federal Funding

Capturing accurate data on racial and ethnic identity through the Census has implications for ensuring fair treatment across the U.S. population, as it is a vital tool in the administration of many federal and state-level programs focused on fighting inequity against marginalized communities, such as the:62

- monitoring and enforcing of equal employment opportunities in education, employment justice, and beyond.

- identification of segments of the population who may not be getting needed medical services under the Public Health Service Act.

- allocation of funds to school districts for bilingual services.

- investigation into whether housing or transportation improvements have unintended consequences for specific groups.

- monitoring compliance with the Voting Rights Act and bilingual election requirements.

The concern of undercounting populations with a combined question format, therefore, poses a real threat of hurting Black Latino communities should their stories become lost in data. Since the OMB announcement, the Afro-Latino Coalition and other advocates have spoken on the implications of this decision for Afro-Latinxs.63 There are concerns that a respondent could designate themselves as Latino but be back coded as a multiracial person if they also choose to designate their race as they had done so on past Censuses.64 There are also concerns that a person may choose to identify with one race alone, such as “white,” but write in the box for a specific origin, such as “Argentinian,” and be back coded as multiracial due to an assumption that Argentinian is a “Latino race,” a concept which does not exist. Additionally, Brazilians remain classified as “White” and not “Hispanic/Latino” under new OMB standards, continuing to misclassify a large percentage of the population.65 While the OMB acknowledges the validity of some of these concerns in their report on the final decision, they fail to provide any current solutions to the back coding issues, stating a need for more research, but no actual plan to conduct said research.66

These issues have the potential to have effects beyond Black Latinos. Some Latinos have also expressed worries about how a lack of transparency about back coding could impact those Latinos who may identify as multiracial. Many Brown Latinos, for example, may continue to mark multiple racial self-identifications, not understanding that under this new format, they may be coded as “two or more races,” as opposed to Latino alone.67 In this single-question format, the question will ask individuals to identify their “race and/or ethnicity.”68 Yet, it remains true that ethnicity is different from race.

“Street Race” as One Way to Improve Data

While the March 2024 decision is solidified for the 2030 Census, the new directive does allow for the addition of other demographic questions.69 Demographic survey formats that allow for the designation of Latino ethnic identity, self-identified race, and street race could allow researchers to better understand the experiences of Latinos across lived experiences and ensure that everyone in the community is accounted for.

Street race, or the race that a stranger would assume you to be based on physical appearance, is a possible solution to improve federal data on race and ethnicity.

Sample phrasing of a question about street race could look like70 (see Appendix A for full question text):

The street race question disrupts the myth of race as a matter of genes or biology by emphasizing the social aspect in how others see your race and that race is a largely visual status.71 While traits such as height, skin tone, or certain diseases can be associated with certain groups that have common ancestral origins, there is no single genetic makeup for a white person, a Black person, or a person of mixed heritage. There is no way to strictly designate “genetic or biological” races.72 Rather, race is a social status that is made up of several factors, including where you are from and what you look like.

Race is often quickly and unconsciously assigned without asking questions about self-identification, ancestry, culture, or genetic makeup. Assumed racial classification has been a basis for interactions between individuals and institutions in our society for centuries, both as a tool for solidarity and oppression. By asking about street race, we gain more insight into how one’s perceived race is observed by others, such as by hospital staff on medical records, teachers, or police officers.

The acknowledgment that Latinos experience society differently based on their visual race is vital in the fight against racism within and against the community. Research shows that Afro-Latinxs experience discrimination and racism differently than non-Black Latinos. In a Pew Research Center report on Afro-Latinx experiences, Black Latinos were more likely than non-Black Latinos to report having experienced discrimination based on race.73 Afro-Latinx individuals’ phenotypic similarities to Black-alone individuals may place them at a higher risk of racism than white Latino individuals in the U.S., which may also be exacerbated by having limited English proficiency or questioning their immigration status.74 Further, compared to non-Black Latinos, Afro-Latinxs have on average a higher poverty rate,75 worse health76 and labor77 outcomes, and experience disproportionate policing.78 In short, Afro-Latinxs face a unique risk of experiencing racism that we must work to further understand in data.

Limited prior research has tested how asking study participants about their street race allows us to further uncover the ways in which our perceived race plays a role in discrimination, regardless of how the person self-identifies. For example:

- In a survey on experiences of discrimination in the employment sector, street race Black respondents were 2.5 times more likely to report discrimination relative to street race white respondents, holding all else constant.79

- In a study on Black women’s experiences with the healthcare sector during pregnancy, Black and Afro-Latina women shared similar experiences of encountering anti-Blackness during pregnancy and birth, even when self-reported racial identities varied.80

- In a study on reported physical and mental health, researchers found significant differences between street-race white vs. street-race non-white individuals on the probability of reporting very good and excellent mental health.81

- A similar study concluded that being classified by others as white is associated with large and statistically significant advantages in health status, no matter how one self-identifies.82

- In a study on healthcare discrimination, racial/ethnic minorities who reported being perceived as white were more likely to receive preventive vaccinations and less likely to report healthcare discrimination compared with those who were perceived as non-white.83

Just as there is no one way to look Latino, there is no one way that Latinos experience racial discrimination. A question of street race would better capture the experiences of communities such as Latinos by revealing how experiences are defined by the race in which they are perceived, allowing researchers in a variety of fields to uncover under-discussed differences within the community.

Further, including “Brown” as a street race category falls in line with the way many Latinos currently see themselves. In a recent Urban Institute National Well-being survey, researchers found “Brown” to be a street race category that resonated with one in five Latino people and that the addition of this category highlighted visible inequities that would have otherwise remained invisible.84

“Brown” has become a more culturally relevant term for Latinos as well as many other groups and should be recognized as such.85 These other groups, such as Pacific Islanders, Southeast Asians, South Asians, Middle Eastern, North African, and Arab communities, are also often undercounted by the Census, and could perhaps benefit from the inclusion of a street race question and Brown identification category.86

The Census has evolved over many iterations in its history. Part of these evolutions should be ensuring that questions match the needs of the current population.

The inclusion of street race does not do away with racial self-identification, but rather acknowledges the continued oppression of visible minorities despite shifts in societal understandings of race. For example, studies show that when mixed-race individuals file discrimination cases, they are often experiencing discrimination because they are racialized as monoracial (e.g., street race Brown or Black).87 Individuals who are of a multiracial heritage may already choose to select only one race when filling out surveys, often based on how they are perceived or what they believe to be beneficial to them or their community.88 By asking about ethnic origin, racial identity, and street race, we can better capture data on how race is encountered and experienced in the daily lives of the U.S. population while still allowing for racial self-identification.

The concept of asking about street race89 is becoming increasingly popular to better understand racialization and disparities, as well as to capture instances of discrimination experienced by visible minorities.90 Recent research that explores street race has been hugely beneficial in unearthing disparities in education equity, housing, criminal justice, and public health.91 Just as we understand the importance of sub-categorizing the experiences of Latinos across different genders or immigration statuses, for example, we must also account for the role that race plays in the outcomes of Latinos and the politics of today.

Policy Recommendations

We offer the following policy recommendations with the goal of bettering outcomes for Latinos of all races in the U.S.:

- The current OMB guidelines do not prohibit adding additional questions on race and ethnicity. The U.S. Census and other demographic data instruments should include a question about street race.

- The federal government should allocate funding to test the addition of a street race question in OMB surveys, including the Census.

- We recommend that a street race question be added to the American Community Survey through the rigorous process of assessment, analysis, evaluation, and implementation already established by the Census Bureau.92

- Because “Brown” is a racial category that is becoming increasingly relevant for Latino populations and other communities, we recommend including it in street race phrasing.

- Street race is a tool for Latino data disaggregation that can apply beyond the U.S. Census. We recommend all researchers work to include a street race question in their demographic questionnaires.

- The federal government should allocate funding to test the addition of a street race question in OMB surveys, including the Census.

- The OMB and the Census Bureau should clarify that race, ethnicity, and nationality are analytically distinct and define these terms for all federal data collection instruments.

- Federal data collection instruments such as the Census and the ACS do not provide clear definitions of the terms race, ethnicity, or nationality,93 instead allowing the general public to interpret the distinction between these terms for themselves. What they do make clear on a website subpage is that “people who identify their origin as Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish may be of any race.”94 However, without a clear understanding of how the Census defines race, ethnicity, and nationality, conflation only continues.

- The use of nationalities as examples of “races” should be eliminated, as it conflates two distinct concepts and may contribute to the falsehood that national origin and race should be concordant.

- The OMB should ensure Census coding procedures accurately reflect racial and ethnic self-identification.

- If one chooses to designate a race and a Hispanic origin, those selections should be respected. OMB protocols for tabulating and presenting survey responses should ensure that certain national origin groups are not incorrectly categorized as “some other race.”

- The federal government should allocate additional funding to advance research on best practices for collecting and analyzing race and ethnicity data.

- The U.S. government should conduct rigorous and representative testing on both the single-question format and the separate-question format to ensure comparative data. This is considering that much of the research is biased towards a single-question format, such as the exclusive testing of Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) category as a race and not an ethnicity.95

- Testing multiple formats would provide better insights into the best methods for collecting data on Black Latinos.

- The U.S. government should conduct rigorous and representative testing on both the single-question format and the separate-question format to ensure comparative data. This is considering that much of the research is biased towards a single-question format, such as the exclusive testing of Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) category as a race and not an ethnicity.95

End Notes

1 Hephzibah V. Strmic-Pawl, Brandon A. Jackson, and Steve Garner, “Race Counts: Racial and Ethnic Data on the U.S. Census and the Implications for Tracking Inequality,” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, vol. 4, no. 1 (December 4, 2017): 1-13, available online; Margo J. Anderson, The American Census: A Social History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015).

2 Ibid.

3 Shereen Marisol Meraji and Adrian Florido, “Here’s Why the Census Started Counting Latinos, and How That Could Change in 2020.” NPR, August 3, 2017, available online.

4 U.S. Census Bureau, “Why We Ask Questions About Race,” November 18, 2022, available online.

5 Nancy López and Howard Hogan, “What’s Your Street Race? The Urgency of Critical Race Theory and Intersectionality as Lenses for Revising the U.S. Office of Management and Budget Guidelines, Census and Administrative Data in Latinx Communities and Beyond,” Genealogy 5, no. 3 (2021): 75, available online.

6 Ibid.

7 Karin Orvis, “OMB Publishes Revisions to Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity,” (White House press release, March 28, 2024), available online; Cristian Arroyo-Santiago, “Opinion: The next Census could reveal a very different America,” CNN, May 3, 2024, available online.

8 For the purposes of this article, we have used the term “Afro-Latinx” to refer to people who identify as Black Latina/o/x/es (unless another term is used in a direct quote to refer to the aforementioned group).

9 AfroLatino Coalition, “Statement from the AfroLatino Coalition on the Updates to SPD 15, Race and Ethnicity Data Standards” (press release, March 28, 2024), available online.

10 For the purposes of this article, we use the term “Latino” to refer to people who identify as part of the Latino/a/x/e and/or Hispanic communities (unless when another term is used in a direct quote to refer to the aforementioned group).

11 Hansi Lo Wang, “The 2020 Census Had Big Undercounts of Black People, Latinos and Native Americans.” NPR, 11 Mar. 2022, available online.

12 The Office of Management and Budget, “Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity,” Federal Register, March 29, 2024, available online.

13 In this report, coding refers to the categorization of Census respondents into designated numerical categories based on their combined race/ethnicity. The majority of Census respondents select one or more of the presented racial categories and are automatically coded into the numerical categories without the need for OMB staff to review the responses – this is called automated coding. All other responses, including those by individuals who designate “some other race,” are coded by OMB staff manually in a process referred to as residual coding or back coding. See Roberto Ramirez, “Coding Operations of Race and Ethnicity Responses in the 2020 Census” (presented to U.S. Census Bureau, 2020), available online.

14 Ricardo Henrique Lowe Jr., “Census Bureau’s Proposal Threatens Integrity of Race and Ethnicity Data,” UT News, December 8, 2023, available online; Ricardo Henrique Lowe, Jr., Yasmiyn Irizarry, Shania Montufar, Edward Vargas, and Nancy López, “Black and Some Other Race?’: Examining Shifts in the Black Latino Population in the Census Bureau’s Modified Race Question,” Center for Open Science, 2014, available online.

15 Ibid.

16 Tanya Katerí Hernández, Multiracials and Civil Rights: Mixed Race Stories of Discrimination (New York, NY: New York University, 2018), available online.

17 Edward D. Vargas, Melina Juarez, Lisa Cacari Stone, and Nancy López, “Critical ‘Street Race’ Praxis: Advancing the Measurement of Racial Discrimination among Diverse Latinx Communities in the U.S.,” Critical Public Health 31, no. 4 (November 27, 2019), available online.

18 Nancy López and Howard Hogan, “What’s Your Street Race?”

19 Tanya Katerí Hernández, Racial Innocence: Unmasking Latino Anti-Black Bias and the Struggle for Equality (Boston, MA, Beacon Press, 2022).

20 U.S. Constitution Article I, Sections 2 & 9.

21 U.S. Census Bureau, “About the Topic of Race,” updated March 1, 2022, available online.

22 Joseph Ahern, “A (Short) History of the Race Question on the Decennial Census,” (Cleveland, OH: The Center for Community Solutions, March 27, 2020), available online.

23 Shereen Marisol Meraji and Adrian Florido, “Here’s Why the Census Started Counting Latinos.”

24 U.S. Census Bureau, “U.S. Decennial Census Measurement of Race and Ethnicity Across the Decades: 1790–2020,” August 3, 2021, available online.

25 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “OMB Directive 15: Race and Ethnic Standards for Federal Statistics and Administrative Reporting,” May 12, 1977, available online.

26 Kim Parker, Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Rich Morin, and Mark Hugo Lopez, “Chapter 1: Race and Multiracial Americans in the U.S. Census” (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, June 11, 2015), available online.

27 Gene Demby, “On The Census, Who Checks ‘Hispanic,’ Who Checks ‘White,’ And Why,” NPR, June 16, 2014, available online.

28 Jacob S. Seigel and Jeffrey S. Passel, “Coverage of the Hispanic Population of the United States in the 1970 Census: A Methodological Analysis,” U.S. Census Bureau, available online.

29 Laura E. Gómez, “Chapter 4: To Count, We Must Be Counted,” in Inventing Latinos: A New Story of American Racism (New York, NY: The NY Press, 2020).

30 Shereen Marisol Meraji and Adrian Florido. “Here’s Why the Census Started Counting Latinos”.

31 U.S. Department of Education, “Final Guidance on Maintaining, Collecting, and Reporting Racial and Ethnic Data,” October 19, 2007, available online.

32 Laura E. Gómez, “Chapter 4: To Count, We Must Be Counted.”

33 D’Vera Cohn, “Census History: Counting Hispanics” (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, March 3, 2010), available online.

34 A recent coding error by the Census Bureau reveals how the Census Bureau understands “Hispanic” or “Latino.” During its data editing process for the 2020 American Community Survey, the Census Bureau did not remove all individuals it would typically classify as “non-Hispanic” or “non-Latino,” including Brazilians and thousands of individuals from Belize and non-Spanish speaking Caribbean countries. This change increased the number of “Hispanic” Brazilians from 14,000 to 416,000. This coding discrepancy underscores that in applying OMB standards, the Census Bureau sees the Spanish language as primary to defining what it means to be Latino. This definition may not match individual understandings of Latinidad, as is the case for many Brazilians. For more information, see Jeffrey S. Passel and Jens Manuel Krogstad, “How a Coding Error Provided a Rare Glimpse into Latino Identity Among Brazilians in the U.S.” (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, April 19, 2023), available online.

35 National Museum of the American Latino, “How Do Latinos Self-Identify?,” accessed March 18, 2024, available online.

36 Christopher L. Busey and Carolyn Silva, “Troubling the Essentialist Discourse of Brown in Education: The Anti-Black Sociopolitical and Sociohistorical Etymology of Latinxs as a Brown Monolith,” Educational Researcher 50, no. 3 (October 23, 2020), available online.

37 D’Vera Cohn, “Census History: Counting Hispanics.”

38 Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6 (July, 1991), available online.

39 Mary E. Campbell and Christabel L. Rogalin, “Categorical Imperatives: The Interaction of Latino and Racial Identification,” Social Science Quarterly 87, no. 5 (November 16, 2006), available online.

40 Howard Hogan, “Reporting of Race Among Hispanics: Analysis of ACS Data” (presented at the Applied Demography Conference, San Antonio, 2014), available online.

41 Christopher L. Busey and Carolyn Silva, “Troubling the Essentialist Discourse of Brown in Education.”

42 Ibid.

43 Nancy López and Howard Hogan, “What’s Your Street Race?”

44 U.S. Census Bureau, “United States 2020 Census,” available online.

45 Ricardo Henrique Lowe Jr., “Census Bureau’s Proposal Threatens Integrity of Race and Ethnicity Data.”

46 Nira Yuval-Davis, The Politics Of Belonging: Intersectional Contestations, (Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2011), 88-93.

47 Afro-Latino Coalition, “Re: Changes to Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race & Ethnicity,” Accessed June 2024, available online.

48 Rachel Marks and Nicholas Jones, “Collecting and Tabulating Ethnicity and Race Responses in the 2020 Census,” Population Division: U.S. Census Bureau, February 2020, available online.

49 Ricardo Henrique Lowe Jr., “Census Bureau’s Proposal Threatens Integrity of Race and Ethnicity Data.”

50 Juan Lozano, “Are Haitians Latinos?” Medium, September 23, 2021, available online.

51 Afro-Latino Coalition, “Re: Changes to Directive No. 15”.

52 U.S. Census Bureau, “About the Topic of Race.”

53 Michelle Wu, “Challenge of the 2020 Census Population Data for Boston, Massachusetts” (Letter to Robert Santos, U.S. Census Bureau, August 15, 2022), available online.

54 Karin Orvis, “OMB Publishes Revisions to Statistical Policy Directive No. 15.”

55 Ibid.

56 The Office of Management and Budget, “Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity,” Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Office of Management and Budget, Executive Office of the President, March 29, 2024, available online.

57 Ibid.

58 Jessica E. Peña, Ricardo Henrique Lowe Jr. and Ana I. Sánchez-Rivera, “Over Half a Million People Self-Identified as Brazilian in 2020 Census,” U.S. Census Bureau, October 24, 2023, available online.

59 Mary E. Campbell and Christabel L. Rogalin, “Categorical Imperatives: The Interaction of Latino and Racial Identification,” Social Science Quarterly 87, no. 5 (November 16, 2006).

60 AfroLatino Coalition, “Statement from the AfroLatino Coalition on the Updates to SPD 15.”

61 Afro-Latino Coalition, “Re: Changes to Directive No. 15.”

62 U.S. Census Bureau, “Why We Ask Questions About Race.”

63 AfroLatino Coalition, “Statement from the AfroLatino Coalition on the Updates to SPD 15.”

64 Tanya Katerí Hernández, “The Magical Transformation of White Latinos into Multiracial Latinos,” Latino Rebels, December 1, 2021, available online.

65 Tanya Katerí Hernández. “The New Census Racial Categories ‘Erase’ Afro Latinos,” The Hill, April 3, 2024, available online.

66 The Office of Management and Budget, “Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15.”

67 Marcela Garcia, “What’s in a US Census Question? If It’s about Race, a Lot,” The Boston Globe, April 1, 2024, available online.

68 The Office of Management and Budget, “Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15.”

69 Ibid.

70 This verbiage is adapted from Dulce Gonzalez, Nancy López, Michael Karpman, Karishma Furtado, Genevieve M. Kenney, Marla McDaniel, and Claire O’Brien, “Observing Race and Ethnicity through a New Lens: An Exploratory Analysis of Different Approaches to Measuring ‘Street Race,’” (Washington DC: Urban Institute, December 2022), available online.

71 Nancy López and Howard Hogan, “What’s Your Street Race?”; Nancy López, Edward D. Vargas, Melina Juarez, Lisa Cacari-Stone, and Sonia Bettez, “What’s Your “Street Race”? Leveraging Multidimensional Measures of Race and Intersectionality for Examining Physical and Mental Health Status among Latinxs,” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 4, no. 1 (2018): 49-66; Nancy López, “What’s Your “Street Race-Gender”? Why We Need Separate Questions on Hispanic Origin and Race for the 2020 Census,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Human Capital Blog, November 26, 2014, available online.

72 David Reich, “How Genetics Is Changing Our Understanding of ‘Race,’” The New York Times, March 23, 2018, Available online.

73 Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, “About 6 Million U.S. Adults Identify as Afro-Latino,” Pew Research Center, May 2, 2022, available online.

74 LaKendra Beard Morgan, Erik J. Rodriquez, Jordan J. Juarez, and Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, “Black Race Matters in the Latino Population,” American Journal of Public Health 114 (2024): 270-275, available online.

75 Misael Galdámez, Morís Gomez, Rocio Perez, Lupe Renteria Salome, Julia Silver, Rodrigo Dominguez-Villegas, Jie Zong, and Nancy López, “Centering Black Latinidad: A Profile Of The U.S. Afro-Latinx Population And Complex Inequalities” (Los Angeles: UCLA Latino Policy & Politics Institute, April 2023), available online.

76 Adolfo G. Cuevas, “How Should Health Equity Researchers Consider Intersections of Race and Ethnicity in Afro-Latino Communities?” Journal of Ethics, American Medical Association, April 1, 2022, available online.

77 Michelle Holder and Alan A. Aja, “Chapter 3: The Labor Market Status of Afro-Latinxs,” in Afro-Latinos in the U.S. Economy (Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2021).

78 Nick Petersen and Marisa Omori, “Unequal Treatment: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Miami-Dade Criminal Justice.” (ACLU Florida: Greater Miami, 2018), available online.

79 Edward D. Vargas, Melina Juarez, Lisa Cacari Stone, and Nancy López. “Critical ‘Street Race’ Praxis.”

80 Shameka Poetry Thomas, “Street-Race in Reproductive Health: A Qualitative Study of the Pregnancy and Birthing Experiences among Black and Afro-Latina Women in South Florida,” Maternal and Child Health Journal 26, no. 4 (July 16, 2021), available online.

81 Nancy López, Edward D. Vargas, Lisa Cacari-Stone, Melina Juarez Sonia Bettez, “Whiteness Matters for Health: Measuring Racialization Among Latinas and Latinos in the U.S. Using Self-Identified Race, Street Race and Ascribed Race,” (presented to Population Association of American, Washington DC, 2015), available online.

82 Camara Phyllis Jones, Benedict I. Truman, Laurie D. Elam-Evans, Camille A. Jones, Clara Y. Jones, Ruth Jiles, Susan F. Rumisha, and Geraldine S. Perry, “Using ‘Socially Assigned Race’ to Probe White Advantages in Health Status,” Ethnicity & Disease vol. 18,4 (2008), available online.

83 Tracy MacIntosh, Mayur M. Desai, Tene T. Lewis, Beth A. Jones, and Marcella Nunez-Smith, “Socially-Assigned Race, Healthcare Discrimination and Preventive Healthcare Services,” PLoS ONE 8, no. 5 (May 21, 2013), available online.

84 Dulce Gonzalez et al., “Observing Race and Ethnicity through a New Lens.”

85 Ibid.

86 Karthick Ramakrishnan, “Census 2020: What’s the Problem with the Asian American Count?,” AAPIdata, February 3, 2020, available online.

87 Tanya Katerí Hernández, Multiracials and Civil Rights: Mixed Race Stories of Discrimination.

88 Nancy López and Howard Hogan, “What’s Your Street Race?”

89 Street race has also been referred to as perceived race, social race, folk race, reflected race, socially assigned race, or ascribed race.

90 Margaret A. Turner, Rob Santos, Diane K. Levy, Doug Wissoker, Claudia Aranda, and Rob Pitingolo, “Housing Discrimination Against Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2012,” (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research), June, 2013, available online.

91 Edward D. Vargas, Melina Juarez, Lisa Cacari Stone, and Nancy López, “Critical ‘Street Race’ Praxis.”

92 U.S. Census Bureau, “How a Question Becomes Part of the American Community Survey,” December 2023, available online.

93 U.S. Census Bureau, “2020 Census.”

94 U.S. Census Bureau, “About the Topic of Race.”

95 Mirna Alsharif, “’We Exist’: New Middle Eastern or North African Census Category Helps Community Members Feel Seen,” NBC News, April 1, 2024, available online.